14. 1. 1991: Milan Kučan receives a uniform for his 50th birthday

In an example of typical Soviet equivocation, the Soviet President attributed the reason for the armed intervention to a "group of workers and intellectuals" who supposedly asked the garrison commander in Vilnius for protection. A phone conversation between Gorbachev and the Lithuanian leader, Vytautas Landsbergis, denoted a quiet recognition of the changed situation after the fiasco, which the former had persistently rejected in recent days.

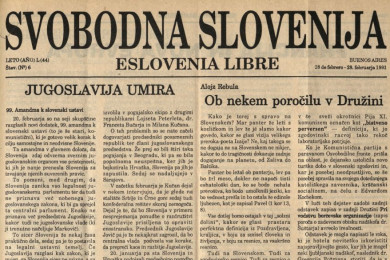

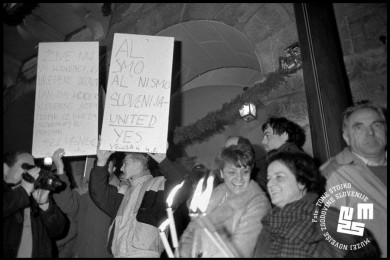

An escalation of the situation in the Baltic only three weeks after the Slovenian plebiscite understandably stirred up the Slovenian public. There was practically not a single political player who would not feel obliged to speak up and the media also dedicated a great deal of attention to the Lithuanian crisis.

But, the response was not unanimous. It seemed that two poles formed, which had already been present, and which remained so at least until the independence. One was based on evident parallels between the Lithuanian and Slovenian situations, due to which their advocates emphasised the urgency of preparations for a similar scenario. Such ideas can be found, for example, in the joint statement of the Social Democratic Party of Slovenia and the Social Democratic Party of Croatia led by Antun Vujić, which stated, "We simultaneously warn all forces which may wish to prevent the further independence processes of Slovenia and Croatia in accordance with the Lithuanian example that we will respond to such pressure with all legal means. We call on the governments of both republics to accelerate the process of extrication from the federation and do everything to protect their democratic societies and all their citizens."

At least partly different was the statement of the Slovenian Presidency, from which the reader gains the impression that the events in Lithuania served particularly as a starting point for other important topics. It seems that it initially wanted to contain the independence euphoria. Although members of the Presidency condemned the violence in the Baltic and highlighted the Lithuanian right to self-determination, they added, "While we condemn any form of violence […], we are at home, in our own republic, obliged to avoid all irresponsible and immature moves that may provoke in us fear, doubt or uncritical enthusiasm in these turbulent times, which has no basis in the actual situation."

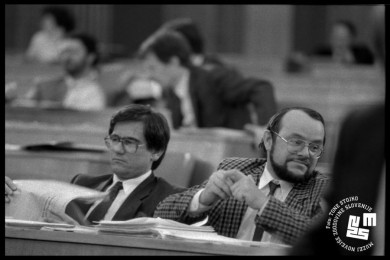

The opinion stated by the opposition party, the Liberal Democracy of Slovenia, that Slovenian policy should not be misled into incorrect assessments and decisions by comparisons with Lithuania, as the situations were supposedly completely different, was even more pronounced. The Party's President, Jožef Školč,explicitly wrote, "Slovenia is not Lithuania and that makes the drawing of parallels between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, which generates fear and a sense of threat, to be superficial and not even in the same wheelhouse." Similar ideas can be found in the statement signed by Borut Šuklje on behalf of the Presidency of the Socialist Party of Slovenia. Certain claims perhaps seemed like a bad joke several months later, as the socialists warned the public that Yugoslavia was not the Soviet Union and that the Yugoslav People's Army was not the Soviet Armed Forces.

On the same 14 January, the debate regarding the image of the Slovenian flag, which had previously begun, now continued. The red star on it posed an issue. After the announcement of the plebiscite results, a dilemma occurred relating to this explicit symbol of the former social system and the post-war Yugoslav state and the DEMOS majority pressed for the adoption of relevant amendments to the Constitution in accordance with a fast-track procedure. The opposition was rather subdued about the removal of the star due to the current situation, but it was still impossible to overlook certain people’s desire to somehow incorporate it into the new era. Referring to the unsuitability of the fast-track procedure was one such method. An "original" argument for the preservation of the star can also be found in the Večer’s article by journalist Tanja Kremžar, who wrote, "Those who say that Slovenia did not have any other flag than this one with the star should be listened to and the tradition should thus not be abandoned so abruptly."

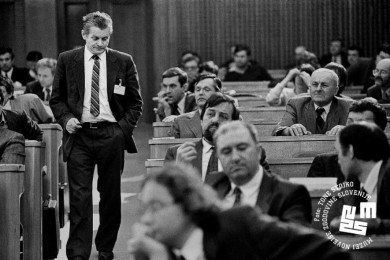

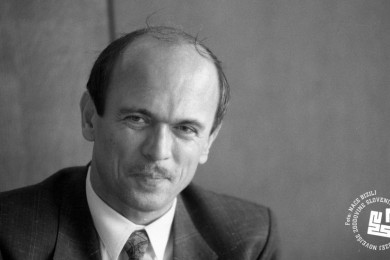

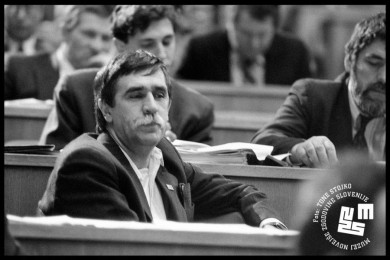

In addition to the developments in Slovenia and worldwide, Milan Kučan, President of the Presidency of the Republic of Slovenia, celebrated his 50th birthday on 14 January 1991. He was honoured, among others, by a visit of the delegation of the Republic Secretariat for People’s Defence led by Secretary Janez Janša. The delegation gave him a prototype of a new uniform for chief officers of the Territorial Defence, which made a strong symbolic impact regarding the ongoing debates at the time.

Author: Aleš Maver

Similar articles

-

Triumphant Year of 1991

-

9. 5. 1991: Facilitated processing of independence laws

-

2. 3. 1991: Slovenians abroad and around the world in concern for Slovenia

-

1. 3. 1991: Franco Juri against the transfer of conscripts to the Slovenian Territorial Defence

-

28. 2. 1991: Prepared defence and protection act proposal to ensure a plebiscite decision

-

27. 2. 1991: The persistently looming red star

-

26. 2. 1991: A hopeless search for the Yugoslav modus vivendi

-

16. 2. 1991: Ciril Ribičič on the red star and reservations about the dissolution of Yugoslavia

-

15. 2. 1991: Two thirds of respondents have faith in an independent Slovenia

-

27. 1. 1991: Between a relaxation of tensions at home and a deteriorating situation in the Middle East