Kolemonov žegen - Book of Magic, Charms and Prayers for Protection

Book of Magic, Charms and Prayers for Protection

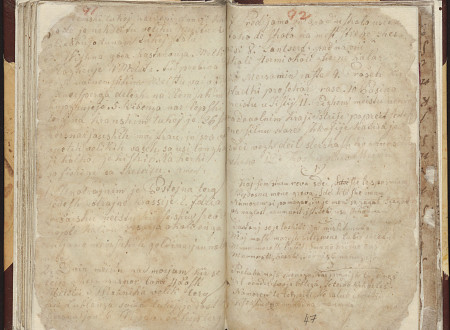

»Kolomanov žegen« is a manuscript entered as item number 202 on the list of manuscripts kept by the Archives of the Republic of Slovenia in its collection of manuscripts. The book includes recordings of folk superstitions that are believed to date back to the 19th century. It was purchased by the National Museum of Slovenia from Dr. Ravenegg and the pencil-written time and place of the purchase on the book's front page (Šiška, 5. 6. 1912) is confirmed also by the stamp of the manuscript’s later owner, the Central State Archives of Slovenia.

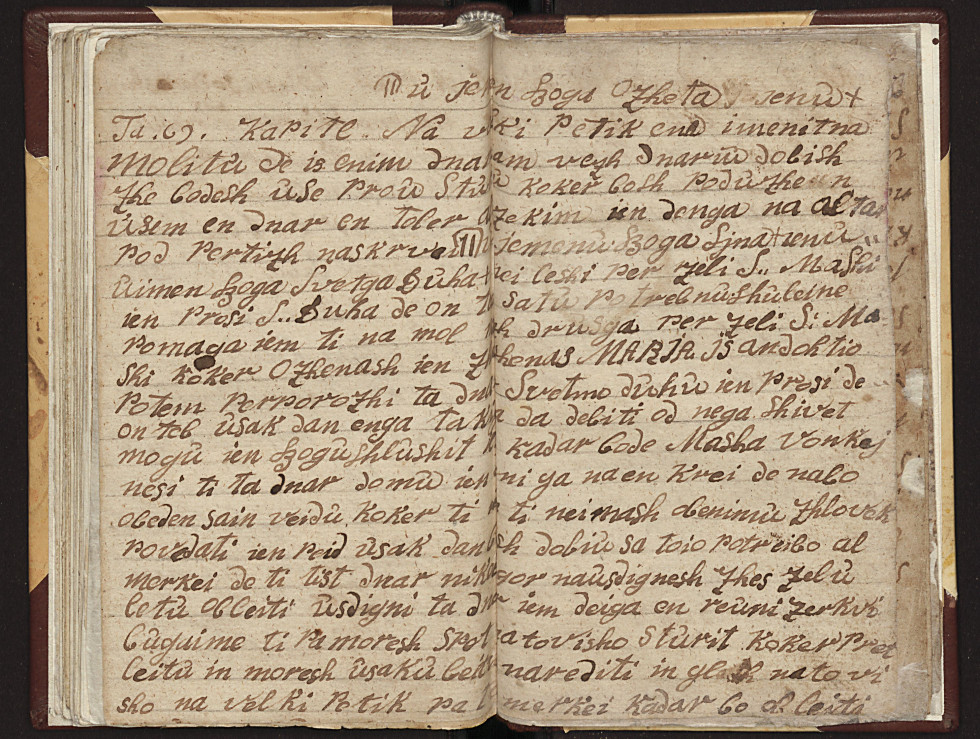

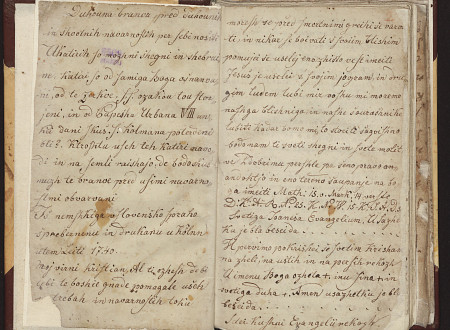

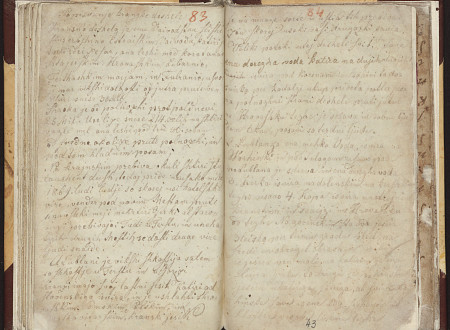

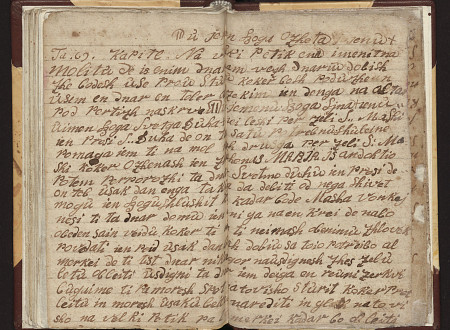

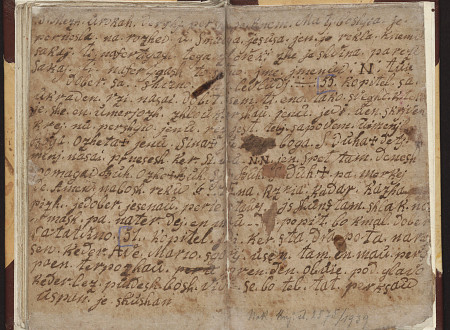

When examining the manuscript I came to the conclusion that its description is incomplete since it does not consider all four of the content sets. The bulk of the book consists of Duhouna branva (pp. 1-82), followed by Popisvanje kranske deshele (pp. 83-92) and the folk poem Ukročena (pp. 92-94). Enclosed to these three sets of numbered pages, all of which were written by the same copyist, are ten non-numbered pages of the individual chapters from Kolemonov žegen. The latter set of pages most definitely does not belong to the original concept of the manuscript.

Apart from their sovereign and the land gentry, people and the economy of the 14th-century Slovenian lands were being heavily oppressed also by the three apocalyptic riders; plague, hunger and death. In the 15th century the army and the new methods of warfare left their mark as well. In the 20th century we might also be able to find the fifth rider, the Spanish flu, and in the 21st century, the sixth one - the not yet fully understood outbreak of coronavirus pandemic.

Slovenian folk tradition has preserved a number of “efficient ways of protection” against various such misfortunes and one form of such protection was also Kolemonov žegen. The original is believed to have been written in Latin. It spread across the German territory and as a translated version found its way from the present-day Carinthia into the territory of today’s Slovenia. The manuscript combined spirituality and mystic past with charms and prayers that were supposed to protect population from any cruel events taking place. It contained a collection of protective prayers, formulas and magic words, superstitions and instructions on how to get the favour of supernatural beings so as to avoid any misfortunes and be successful in acquiring earthy material goods. Soldiers were particularly fond of it, since they were the ones who most needed protection from the enemy’s weapon, from wounds, from dying on the battlefield or from being left crippled, which led to them being discharged from the army and having to spend their life in poverty as beggars. To ward off danger, Kolemonov žegen was also used by pilgrims; those who went on a pilgrimage to German Köln, Aachen and Trier, as well as the ones making a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. Protection of this sort was also sought by other travellers, horse-drawn carriage drivers, and farmers in their care for their own health and for the health of their livestock, which was of vital importance for their survival.

The majority of the manuscript’s content speaks for itself: Duhouna branva, pred duhounih in šhodnih navarno∫tih per ∫ebi nositi. U katirih ∫o mozhni šhegni in shebraine, katiri ∫o od ∫amiga Boga ošnanovani, od te Zerkve, S. S. ozakou tou ∫torjeni, in od Papešha Urbana VIII unku dani, ∫kuš S. Kolmana poterdeni bli. Z Ktro∫htu u∫eh teh, Katiri na vodi in na ∫emli raishajo, de bodo ∫kus muzh te branve prad u∫imi navarno∫tmi obvarvani. Is nem∫hkiga u ∫lovenško ∫praho šprebernenu, in drukanu u Kölnn u tem Leiti 1740. Moj virni Kri∫tian, Al ti ozhe∫h de bi tebi te boshie gnade pomagale ušeh potrebah in navarno∫tih toku moze∫h se pred ∫mertnimi greihi še varvati … Also included in the text are apocryphal prayers, blessings and gospels that contain both superstition as well as pragmatic Christianity and simultaneously juxtapose protection charms against witchcraft with Christ’s dying words on the cross. Technically, they are separated by a space between the lines or by marks signalling the end of the page (eg. †††). There follows a short chapter titled Popisvanje kranske deshele in which the same author describes the Duchy of Carniola from an administrative, religious, geographic and economic point of view. Placing special emphasis on Upper and Lower Carniola, this chapter ends with the description of Postojna and Predjama Castle. With no particular space between the lines there follows a sixteen stanza folk poem “Ukročena”: Kaj sem stara reva sdei, ∫he le spoznam Preposnu mene greva , ∫dei k te ∫he imam …

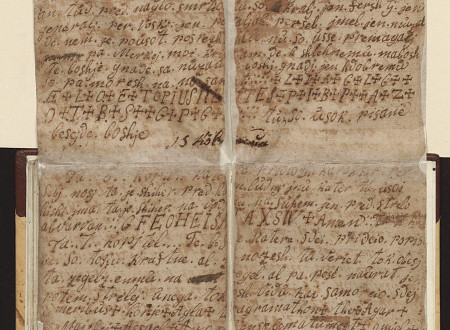

Added at the end of the manuscript are non-numbered pages with individual chapters from Kolemonov žegen. Two printed copies of Žegen have already been digitized and are available online on the portals of the National and University Library and of the Carinthian Central Library in Ravne. Both copies are a century older than the one preserved at the Archives RS and have the same content. Written in Bohorič’s alphabet with occasional use of other letters as well, the two copies have a similar form as prayer books (71 chapters, 283 pages). Individual chapters are further divided into requests for different blessings and into kolzhanza oz. kolhenzna. Kolhenzna means to conjure, a lock, a spell, etc. - a conjuration with intercession for divine, mystical help. This is followed by the Stations of the Cross with shebranje, i. e. fast and monotonous prayers at the Stations of the Cross, and prayers to patrons for different purposes. Finally, there are some images of St. Josef, St. Ignatius, and St. Sebastian.

In addition to printed booklets, there were a number of manuscript versions of the text circulating among country folk as well. Such manuscripts are not well preserved, their initial and end pages are often missing and whole chapters of the book are sometimes edited or even omitted. They are written in dialect and the abilities of their copyists are sometimes questionable, judging from their failure to use punctuation marks and capital letters or from occasional use of wrong letters. The tradition of copying, the so-called Carinthian bukovniki literature, evolved from the works of Slovenian Protestants, whose influence should not be overlooked. Experts and scholars of Slovenian and Slavic languages, ethnologists and historians all agree that different copies of Kolemonov žegen characteristically show the development of the Slovenian language, word-formation and script, as well as depict the spiritual and economic picture of Slovenian territory from the second half of the 18th century to the end of the 19th century. Several articles have been published so far on the topic of comparing different versions of the text with supposedly the earliest Carinthian version of the text, which is believed to originate in the vicinity of the Lake Wörth.

Our case is a selection of twelve (of total 71) shortened chapters. One of them goes as follows: Ta 6. Kapittel. Katir. Te. Puhstabe. Per Sebi. Nossi. ta. bo. Pred. u∫sim. hudim. Inu. Pred. strelo. obvarvan. GFEOHEISAI. 3 TA XSW † Amen. Texts for warding off danger in other chapters are »strong words«, which together with intercession and prayers would offer protection against evil people and sudden death, offer instructions on how to break a spell over livestock, how to find ore, and in chapter 51 also instruction on how to obtain 90,000 ducats. The instructions on how to pray and conjure had the desired effect only when people carried with them the written texts as well. Judging from the different formats of the paper, different text layouts, different writings, and even duplication of three chapters, I can conclude that in this case several contemporary copies were placed together, but the person making these copies was not the same. Their physical state of preservation gives the appearance of frequent use.

The whole manuscript reminds one of a manual which in a unique way describes faith in Duhouna branva and in several chapters of Kolemonov žegen, as well as provides geographic description of the land of Carniola, and finishes off with some folk tradition in the form of a folk poem. Based on the style of writing and the dates that appear in the text, I believe the manuscript dates back to the second half of the 19th century.

Gašper Šmid