Plans for the Baraga Seminary

Ljubljana, 1937-1939

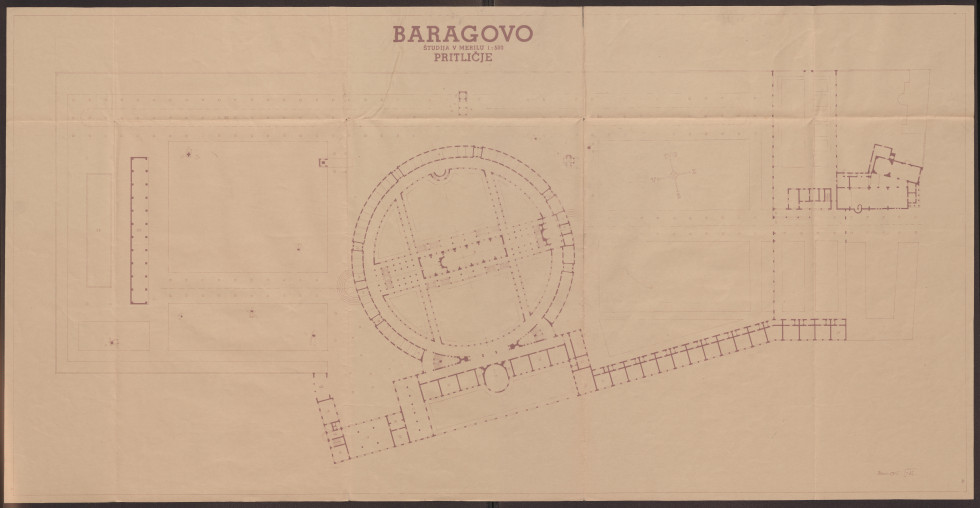

Original, 3 plans, 46 x 90 cm (study of the ground floor), 64.5 x 155.5 cm (frontage), 63.5 x 116 cm (position, cross section), architects Jože Plečnik and Anton Suhadolc

Reference code: SI AS 73, Kraljevska banska uprava Dravske banovine, Tehnični oddelek, fasc. VI/4, Sarta tecta: Ljubljana - Baragovo semenišče

Plečnik's idea of the circular design of the Baraga seminary comes from monastic architecture. | Author Arhiv Republike Slovenije

In the 1930s, the Ljubljana Diocese chose the abandoned cemetery of St. Christopher, located in the Bežigrad district in Ljubljana, as a site where a new seminary was to be built, named after the Slovenian missionary Friderik Baraga. Architect Jože Plečnik was commissioned to draw the plans for the seminary, but the great master was reluctant to undertake this new project, since it did not correspond with his overall conceptual design idea for the Bežigrad district. His original plan for the district was, among other things, to build the House of Glory, a sacral building marking the final resting place of some of the most prominent and famous Slovenians. He was able to partially realize this idea by creating the Navje Memorial Park, which he pushed to the far right (eastern) edge of the cemetery.

In 1936, Plečnik drew the plan for the “Baraga” seminary at a scale of 1:500. What he envisioned was a four-storey circular building, connected in the middle by transversal tracts, and on the northern side there was to be a rectangular connection, leaning against the newly developed Linhart Street. The circular part of the building was to accommodate rooms for the students of the seminary, and the central transversal tract was to house a chapel and a hall. In addition to the central tract, Plečnik at first envisioned additional two tracts, connected with the central tract to form a letter H within the circular part of the building. Later, he abandoned the idea of additional tracts. The rectangular tract, which was to run along the Linhart Street, was to house administration, classrooms, a kitchen and staff quarters. In Plečnik’s floor plan of the seminary, we can notice the outline of the Greek letters alpha (A), omega (Ω) and theta (Θ), which reflects his striving for symbolic connection between perfection and God.

Apart from the aforementioned plans, Plečnik did not produce anything else. Since his plans were not a sufficient base for the start of the actual construction process, Anton Suhadolc had to come up with more detailed plans, which led to the deterioration of the already strained relations between the two architects, and eventually caused Plečnik to give up the project and its authorship altogether. In his letter to Suhadolc in December 1938, Plečnik wrote:«… I cannot say if the building is being built according to my plans – But if this is the case, it is done without any reworking from me, without my details, etc. […] Baraga Seminary is a corpse to me – I hope to God that it is life to all of you. Let us not discuss this further. Respectfully Plečnik«.

Using Suhadolc's plans, the building of the seminary began in 1938 and by the end of the autumn of 1940, half of the circular building was already standing. The owners planned to move in the following school year and by the start of 1941, there were plans made for the building of the northern part. The actual construction of the northern part itself, however, was detained due to the onset of the war. The seminary has to this day remained built to this phase and no further, and none of the seminarists have ever set foot in the building. Even after the war, the building never served the purpose for which it was built, because in the 1950s the architect Anton Bitenc converted it into a student dormitory, which to this day shares its space with Pionirski dom – Centre for Youth Culture and with the Slovenian Youth Theatre. By 2025, the municipality of Ljubljana intends to renovate and complete the construction of the building as envisioned in Plečnik's plans.

Despite Plečnik's disagreement with the new plans, we can still undeniably see his influence on the finished building. The main staircase with landings on each side is supported by columns made of marbled and polished plaster (the so-called stucco lustro technique), finished with Doric capitals. The exterior of the building also bears witness to Plečnik's idea of the four rows of windows, interrupted periodically by inset balconies. There was also a bell tower standing above the chapel in the central tract, but it was pulled down during the Bitenc renovation.

Vanja Rupnik

- Hrausky, Andrej: Plečnikova arhitektura v Ljubljani. Ljubljana: Muzej in galerije mesta Ljubljane, Galerija DESSA, 2017.

- Krečič, Peter: Jože Plečnik. Ljubljana: DZS, 1992.

- Prelovšek, Damjan: Jože Plečnik: arhitektura večnosti: teme, metamorfoze, ideje. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC, 2017.

- Potočnik, Tina: Če Gospod ne zida hiše, se zastonj trudijo oni, ki jo zidajo: Baragovo semenišče v Ljubljani. In: Arhivi 44 (2021), no. 2, pp. 421–439.