»For Right-Wingers, PEN is Too Left-Wing, and for Left-Wingers it is Too Right-Wing«

Archival Source

Ljubljana, 1962

Original, paper, 13 pages

Reference code: SI AS 1931, Republiški sekretariat za notranje zadeve SRS, box 1679, description unit 33

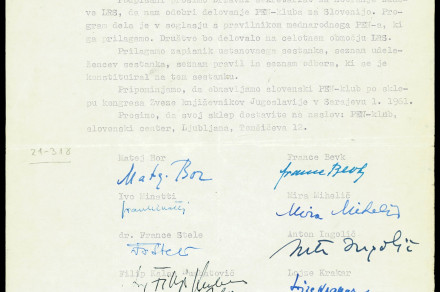

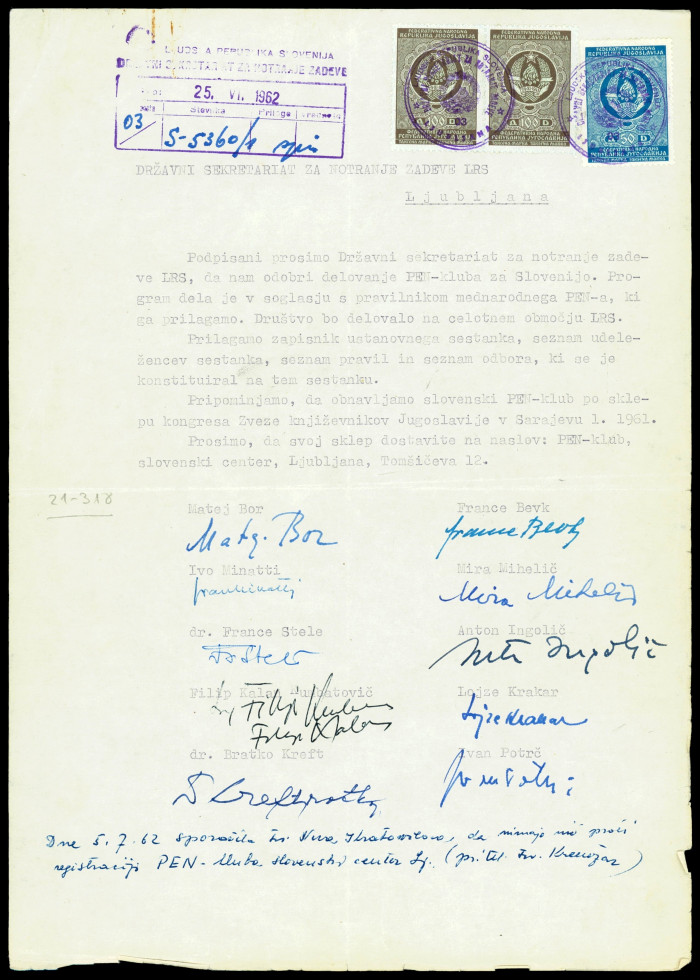

The request of the initiative committee for the relaunching of the PEN Club - Slovenian Centre Ljubljana, June 25, 1962. | Author Arhiv Republike Slovenije

60 Years Since the Re-Launching of the Slovenian PEN Centre

In 1921, more than a century ago, an organization came to life in London, which in the spirit of friendship and interconnectedness of writers in the divided post-war Europe was founded by some of the most prominent English writers of that time. The newly-established club bore the acronym PEN and was a safe haven for poets, essayists and novelists (Poets-Essayists-Novelists). From the very start, the goal of the club was to surpass boundaries and stand up for freedom of speech, for peace and friendship among all writers, regardless of their nationality, race, religion or political system in which they reside. The London based PEN quickly outgrew its frames and earned international acclaim. Only five years after its establishment (in 1926), it welcomed the Slovenian PEN branch in its midst, whose first president became the Slovenian poet Oton Župančič. Although Slovenian PEN turned out to be an important social factor in the events preceding WW2 by successfully defending the persecuted writers from Primorska region and even being among the initiators of the first international condemnation of Fascism and Nazism at the 1933 PEN congress in Dubrovnik, the centre ceased its operation at the start of the Second World War. It wasn’t until 1960s that the club finally re-launched its activities. This month’s archivalia describes the efforts put in by Slovenian writers to re-launch Slovenian PEN Centre and offers an insight into the background of the operations of internal affairs authorities in regard to its registration.

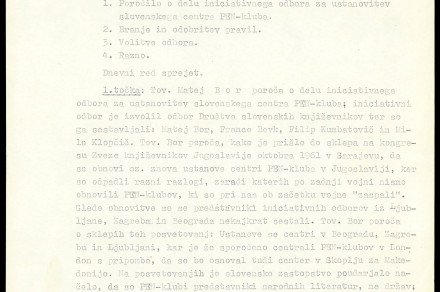

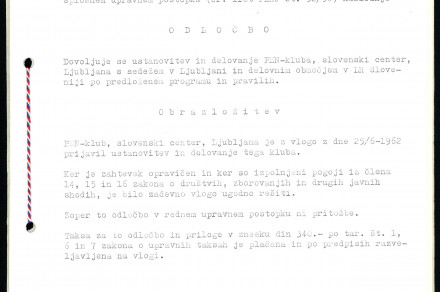

On June 25, 1962, ten Slovenian writers - Matej Bor, France Bevk, Ivan Minatti, Mira Mihelič, Anton Ingolič, Filip Kalan-Kumbatovič, Lojze Krakar, Bratko Kreft, Ivan Potrč and France Stele - submitted a request for the registration of PEN club – Slovenian Centre Ljubljana (later Slovenian PEN Centre) at the State Secretariat for Internal Affairs of the People's Republic of Slovenia. Attached to their application, in accordance with the provisions of the Associations, Assemblies and Other Public Meetings Act (Official Journal FLRJ, no. 51/1946), were the minutes of the club’s founding general meeting (of April 5, 1962), a list of all thirty participants of the founding assembly, a list of elected committee members, the rules of the club and its work plan. It seemed that the applicants managed to comply with all legal requirements, and on July 6, 1962 the state secretariat granted their request and issued a decision, allowing the club to be established. However, judging by the archival records kept at the Archives of RS, the state secretariat quickly revoked its decision. This was the start of months-long outplaying, during which public and state security authorities checked for potential harmfulness of the club's activities and navigated among various political interests. As was observed by Janez Menart at the 1993 mourning session held at the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts in commemoration of Matej Bor’s death, the federal politics “was rather opposed to the re-launching of the Slovenian PEN Centre, as it saw it as a basis for political confederalism”.

The initiative to re-launch PEN clubs in Yugoslavia was first raised in October 1961 at the congress of Yugoslav writers in Sarajevo. The participants agreed that as representatives of national literature, PEN clubs played an important part in raising awareness about Yugoslav culture in international community. Initiative committees were formed to establish Yugoslav PEN club and its four independent centres – Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian and Macedonian. These were to be autonomous and have their headquarters in Ljubljana, Zagreb, Belgrade and Skopje. However, the formation of the Yugoslav club and the four national centres did not go smoothly or without any complications. When speaking for the newspaper Delo in March 1962, the poet Matej Bor, Slovenian representative in the Yugoslav initiative committee, admitted that different opinions regarding the organization of PEN club had come to the surface – from unitarian tendencies to demands for a centralized leadership, or questions as to which national centre Montenegrin and Bosnian and Herzegovinian writers, who didn’t have their own centre, should join. These issues mirrored the Yugoslav social situation of that time. Ideological and political direction of the international PEN proved to be problematic as well. “For right-wingers the PEN club is too left-wing, and for left-wingers it is too much of a right-wing institution …” spoke Bor for the newspaper Delo in March 1962, just a couple of days before the founding session of the Slovenian centre. According to the data provided by the club’s general secretary David Carver, in 1962 the International PEN (International Association of Poets, Playwriters, Editors, Essayists and Novelists) had “over 70 centres in around 55 countries”. It was “a melting pot” of different ideas, ideologies and ideological and political concepts. It stood for values that were surely foreign to the Yugoslav authorities at the time, since among other things it fought against censorship and for the freedom of speech.

It was precisely because of this mentality, which Yugoslav authorities at the time found rather unsettling, that the Slovenian PEN Centre found itself under the scrutiny of the public and state security authorities. Its re-launch was even discussed by some of the more prominent figures of the then political establishment. After the premature granting of the request by the state secretariat for internal affairs, which allowed the club to continue with its activities, there was a frantic exchange of reports and opinions as to the potential harmful effects of the club’s operations. People in power analysed articles about the issues of PEN in Slovenian media – such as Bor’s and Carver’s interview for the newspaper Delo, or the critique written by Slovenian writer Vladimir Kavčič in the magazine Mlada pota, in which he argued about the establishment of a new Slovenian “literary elite”. As far as the State Security Administration and Public Security Administration were concerned, there were really no formal reservations about the club’s registration. Nevertheless, the matter came to a sudden stop. In the second half of July 1962, Matej Bor contacted the head of the registration procedure Stane Kremžar, informing him that the deadline for the decision was about to expire. He pointed out that, before submitting formal request, he had received personal assurances from Boris Kraigher and Ben Zupančič that they would support the founding of the centre. He wished that the request for registration would be granted at a time when David Carver, General Secretary of the International PEN, was visiting Slovenia, having accepted the invitation extended by the Slovenian Writers’ Association. Since this was not very likely and since Bor obviously did “his homework”, Kremžar contacted Rik Kolenc, assistant state secretary for internal affairs, asking his advice as to how to handle the situation. It was decided that they would ask the applicants to formally complete their application, claiming that it had not been made in accordance with the legislation. This bought them some time, since all formal deadlines were then temporarily stopped.

The State Secretariat for Internal Affairs then contacted the Executive Board of the People’s Assembly of the People’s Republic of Slovenia. On July 25, 1962, its State Secretary Vladimir Kadunc brought the issue of club’s registration to the attention of the Internal Politics Committee, and asked for their comments. Although the Executive Board did not meet during summer, as it was on summer break until August 31, it seems that the internal affairs authorities were finally given the green light. Namely, on August 15, 1962, the State Secretariat again issued their decision to the Slovenian PEN Centre, approving its operation.

However, the ordeal of founding Slovenian PEN Centre was still not over. Only a week after the second decision had been issued, the Slovenian PEN Centre again received a call to yet again complete their registration application. Apparently, the data in the original application was insufficient. These shortcomings, however, would have made it impossible to issue the decision in the first place. Correspondence between both parties reveal that the process of solving open questions continued up until November 1962.

Slovenian PEN Centre was obviously a thorn in the side of Yugoslav politics as well as the cultural elite, since it was an indication of the wish of Slovenian people to strengthen their own identity within the federation. On the other hand, re-launching of Yugoslav PEN clubs was in the interest of the International PEN Club, since Yugoslavia at the time of the cold war was in a unique position to act as a bridge between two opposing blocks. An opportunity to do just that arose in 1965, when Bled was chosen to host the 33rd international PEN congress. It was to be the first time that writers from the Western as well as the Eastern block had a chance to cooperate. This, however, is a story for another archivalia of the month.

Gregor Jenuš

Sources and literature

- SI AS 1931, Republiški sekretariat za notranje zadeve SRS, box 1679, description unit 33.

- Aščić, Jelena: Blejski ognjemet v času hladne vojne. 33. mednarodni PEN kongres na Bledu leta 1965. Ljubljana: Filozofska fakulteta, 2016.

- Menart, Janez: »Poslovilne besede«. In: Sodobnost 41 (1992), No. 11/12, pp. 911–915.

- »Krepitev mednarodnih zvez – Jugoslovanski književniki v PEN-klubu – Razgovor z Matejem Borom«. In: Delo, 31. 3. 1962, No. 89, p. 5.

- »Pomoč literaturam malih narodov – Razgovor z generalnim sekretarjem PEN kluba D. Carverom«. In: Delo, 18. 7. 1962, No. 195, p. 6.

- Slovenski center PEN.

- PEN International - Our History.