Instruction for Sugar-Free Canning of Fruit

Letter from the Imperial and Royal Office for Public Nutrition regarding the use of sugar. | Author Arhiv Republike Slovenije

The war, which most assumed would be no more than a short retaliation for the assassination of the Austrian heir to the throne, dragged on for three years. Situation in the Balkans had damaged Habsburg economy even prior to World War I, but now the increased military need for food, clothing, firearms and medicine made it even harder for civilians to get access to such necessities. There was shortage of male manpower, of draught animals, and of fodder and fertilizers, which in turn forced women, children and elderly to work “more that anyone could expect them to”. Agriculture was criticized for failing to do its job, as hunger spread throughout countryside, where many farmers went hungry due to the requisition of food. In 1917, spring was delayed, growth was poor, and on top of it all, there came a period of severe drought. In Dalmatia it hadn’t rained from April until mid-June, and in Carniola, grains were low, wheatears modest, and potatoes took ages to come out of the ground.

Ever since the start of the war, all matters concerning economy and food supply were decided by the central government in Vienna. To prevent reselling and inflation, they followed the German example and began establishing military-economic head offices for individual food products. Locally, requisition commissions implemented central instruction of submitting crops at set maximum prices, and municipal and supply committees took care of the distribution of food. Compared to the power of war bureaucracy, the role of ministry of agriculture and agricultural representatives was sort of pushed into the background.

Although the prices of flour and grain were being regulated already by December 1914, by the end of 1916 they still managed to increase sixfold and by the summer 1918 there was a tenfold, sometimes even twentyfold increase in prices (Carinthia). In Ljubljana, the town supply centre controlled market prices, opened a state war shop in 1915 and a state bakery in 1916. In 1916, people had to use coupons to buy flour, bread, meat, sugar, and potatoes, provided they were available at all. Matters were made worse with each passing year, and towns began facing irregular supply of their allocated quota of provisions.

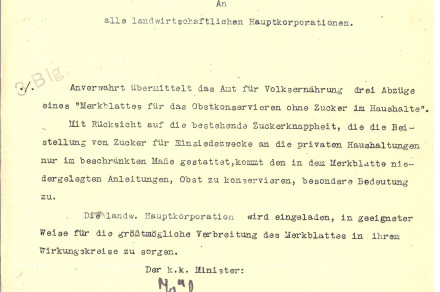

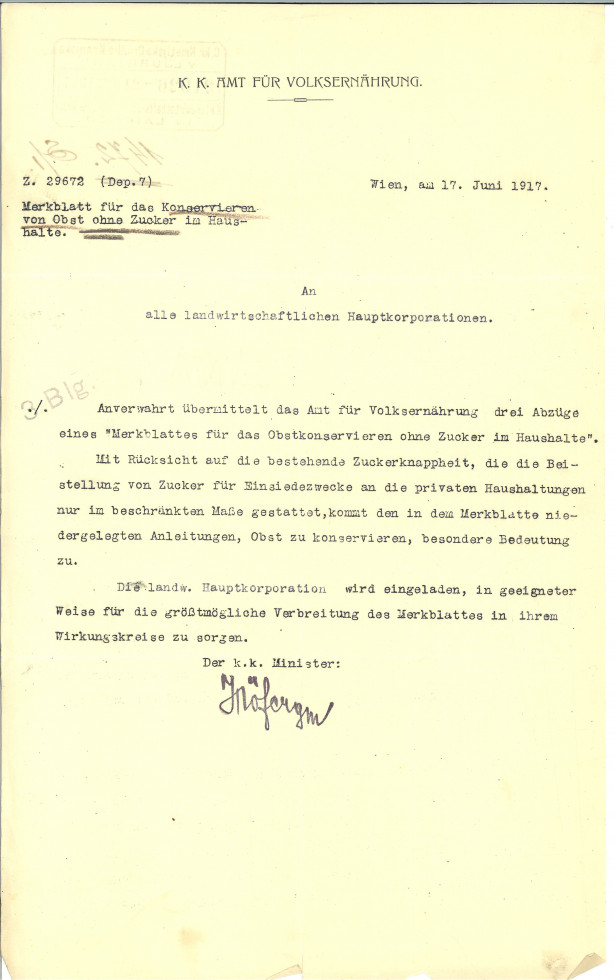

In this state of general shortage, the Imperial and Royal Office for Public Nutrition focused its attention to fruit as well. In May 1917, the office issued a regulation on fruit trade, allowing the trade to be conducted only by those who obtained permission of the district board and the “vegetable and fruit supply office”, which was authorized by the imperial office in Vienna; in Carniola this role was carried out by the Carniolan Supply Company in Ljubljana. In mid-June, two days after the regulation had come into force, the Imperial Office for Public Nutrition sent to all major Carniolan agricultural corporations a letter and enclosed to it some instructions on how to can fruit without using any sugar. They urged the recipients of the letter to pay special attention to the issue in question, since sugar was an increasingly rare commodity in any household (in March 1916, people could only purchase it with coupons, rationing a kilo of sugar per person every four weeks). In the letter, the imperial office urged the district offices to disseminate these instructions across the territory of their jurisdiction. One copy of the letter was also received by the “Imperial Royal Agricultural Society for Carniola in Ljubljana” and we have chosen it for this month’s archivalia.

The seriousness of sugar shortage and importance of fruit is further supported by the fact that a month after receiving the aforementioned instructions from the Austrian central office, Carniolan Agricultural Society received additional three copies of the same instructions from the Carniolan provincial government, together with an introductory letter in which the government officials summarized the instructions received by their Austrian superiors.

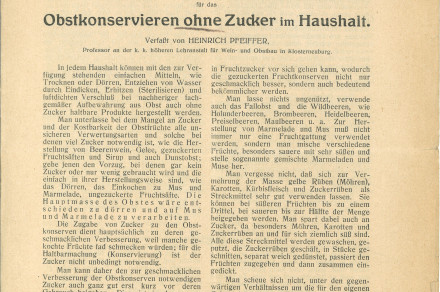

Although bureaucracy tried to move fast, profession managed to stay a step ahead of it. Namely, on June 15, two days before the instructions had even been written in Vienna, Carniolan agricultural society already produced an article on the canning of fruit without sugar and even published it in its official journal Kmetovalec. It is clear from the content that the article’s author, Carniolan fruit supervisor M. Humek, had in his hands the same instructions as his Austrian colleagues. These instructions were written by Heinrich Pfeiffer, a professor at the Imperial and Royal Higher School for Fruit and Wine Growing in Klosterneuburg, the first specialized secondary school in Austria where a number of Slovenian experts on cellaring, winegrowing and fruit growing studied. To make his readers enthusiastic about sugar free canning of fruit, Humek explained why and how (canned) fruit can go bad, he listed preservatives that are harmful to our health, and enclosed instructions on how to hermetically seal all sorts of cans.

If our present-day sugar overloaded society inclines towards reducing consumption of sugar to achieve health and beauty ideals, our predecessors during WWI had to manage without it, because it was simply not possible to obtain it anywhere. When the war broke out, sugar was the first thing to run out in Great Britain (since three quarters of it were imported from Austria-Hungary and Germany). From 1916 on, even people of Austria-Hungary could only purchase it with coupons. On June 9, 1917, the Imperial and Royal Office for Public Nutrition allocated to Carniola ten wagons of sugar to be used in fruit processing. This consignment of sugar, however, was only intended for large manufacturers, while households in cities and industrial centres as non-producers would have to go without. Carniolan Agricultural Society wrote two letters to the Carniolan government, urging it to change this instruction from Vienna. They claimed that it was precisely those households in towns and industrial centres that did most of the preserving and canning of food, since farmers usually did not have enough practice (only wives and daughters who attended housekeeping schools and courses had some experience with such processing of food) or time (with all the extra work on stubble crops), while industrial processing was virtually non-existent (the number of those who grew vegetable and fruit in school or parish gardens was almost not worth mentioning). They proposed distributing sugar among households depending on the number of family members. In return, households would sell to the state supply committee one hermetically sealed can of whichever product they made out the received sugar for each kilo of received sugar. On July 2, 1917, Gustav Pirc, the general head master of the Carniolan Agricultural Society, was invited to attend the meeting of representatives of independent farmers that took place at the Austrian agricultural ministry in Vienna. He was there as a spokesman for the Southern crown lands and made a personal appeal for Carniolan households to be given sugar so they could can fruit and make petitot – which was a sort of “wine” made from grape skins, sugar and water (in fact, at the end of that same month Carniola was allocated some 20,000 kg of sugar precisely for the making of petitot)

Now we are probably all curious about how, more than a century ago, our grandparents managed to can fruit without sugar and prevent it from going bad. They specifically stated that sugar is not always necessary to preserve fruit, which is something we understand when it comes to drying of fruit. However, when making marmalade, apple sauces, juices or when canning fruit without any water, the preservation of fruit was achieved mostly by hermetical sealing and sterilization. To be even more certain that fruit in such cases is well-preserved, people often made use of sodium benzoate, and, since they were unaware of its damaging effects, instructions prescribed ten times more of it than is allowed today. Instructions also suggested how to increase the quantity of a product by adding sweet fruit fillers made of carrots, turnip-cabbage, sugar beet or pumpkin. Perhaps our readers may also find it interesting to find out how to prevent apple slices from turning brown by using a solution of kitchen salt. You can find out more about it in the attached Slovene translation of the original record.

Aleksandra Mrdavšič