»… and they returned home without being medically examined …«

»… and they returned home without being medically examined …«

With the withdrawal of the German troops in November 1918, the First World War – the war that was to end all wars – finally came to an end, leaving in its wake a trail of devastation and poverty, tens of millions of dead and wounded, and peace that seemed anything but permanent. But before the war was over, humankind was struck with another catastrophe as a particularly serious form of flu also joined the dance of death that was taking place during the second decade of the 20th century.

This flu of unidentified geographical origin, which was named the Spanish flu only because in the neutral Spain it was possible to write about it without any censorship, first appeared in the Slovenian territory in the summer of 1918. The newspapers at the time reported that although the “Spanish” was highly contagious, the first wave of the outbreak was not deadly. By September of that year, however, the virus began to show its more sinister side, resulting in the death of a two-year old boy and probably also that of a twenty-year old girl, who had died of pneumonia two days before the boy. In the Slovenian territory the Spanish flu is estimated to have claimed some 6000 lives, pneumonia being the main cause of death. The death toll was particularly high among the young, school children and young adults aged between 20 and 30, whose excessive immune system response or cytokine storm, similarly as in COVID-19, caused pulmonary edema and led to death by suffocation. Among the undernourished and war stricken population of Europe the disease spread rapidly, greatly assisted also by the armies of soldiers returning home from the font, by political changes weakening the work of health care service, and by powerlessness of the doctors faced with the unknown cause and pathology of the disease.

In Austro-Hungarian countries the handling of infectious diseases was regulated by the 1913 Act on the Suppression of Infectious Diseases. This act, however, did not include provisions for the flu, despite the fact that the illness tended to reappear in increasingly serious forms every few decades or so. At the end of October 1918, the Ljubljana city doctor believed that there was no official way for the public health system to fight the influenza outbreak. Instead, recommendations were issued, advising people to avoid crowds, socializing and contacts with the sick. People were advised to keep personal hygiene, to regularly wash their hands, gargle disinfectant, and to air public spaces as often as possible. The authorities would only consider other measures, such as closing down of the cinemas, theatres and tram, if the flu reappeared in a more serious form.

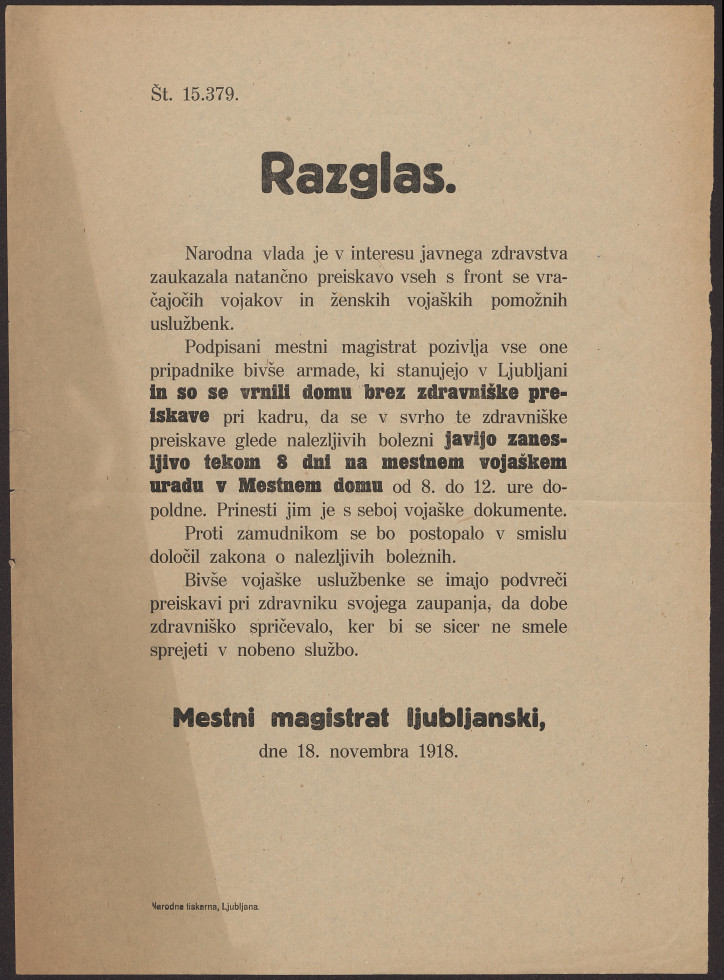

After about two months, by mid-November 1918, the second wave of the epidemic in the Slovenian territory was more or less over. Since this deadly epidemic of flu was over as quickly as it came, the only measure officially adopted by authorities to protect the public health was to close down all schools. Schools were closed down at the beginning of October, at the height of the epidemic. Children thus left school in Austria-Hungary and returned to it in the newly founded State of Slovenians, Croats and Serbs. The fact that the Spanish flu epidemic was of short duration here is furthermore confirmed by the fact that celebrations that took place at the formation of our new state did not have much impact on the spreading of the disease. Still, the National Government of SHS in Ljubljana did not leave epidemiological picture to chance. The return of soldiers from the front was in full swing, and so was a probability of various diseases being spread among the general public. To prevent this from happening, the government issued a decree, published on November 15, 1918 in the Official Gazette no. 7, by means of which it was obligatory to undergo physical examination for those returning from the front line and for those who had already returned but had not been examined yet. Potentially sick were to be immediately sent to a hospital and were to stay there until they were cured or no longer contagious. The duty of enforcing this state decree was assigned to local authorities. Public proclamation of one such authority, the Ljubljana Town Hall, is preserved by the Archives of the Republic of Slovenia in our Collection of posters, leaflets and calendars. Men who served in the former Austro-Hungarian army had to report to the city military office, and women were to call on their personal physicians. If they failed to do so, the former faced penalty or imprisonment, while the latter were prevented from finding employment without official medical certificate of health.

By November 18, 1918, when the Ljubljana Town Hall ordered the men and women of Ljubljana to take obligatory medical examination, the second wave of the epidemic was already over. The virus, which today is known to be influenza A virus subtype H1N1, eventually mutated into a less aggressive form that in February 1919 led to the third, non-deadly wave. Between 1918 and 1920, once it spread throughout all the continents, the Spanish flu is estimated to have claimed 50 to 100 million lives, which is one to three times more than the number of lives lost during the Great War. Despite these numbers, the epidemic of Spanish flu seems to have slipped from the people’s and partly also from the history’s memory; apart from taking place during one of the turning points in man’s history, it was merely another among a number of life-threatening hardships troubling the world population in 1918. Once its grip loosened, it was immediately replaced by a new kind of trouble.

Anja Paulič