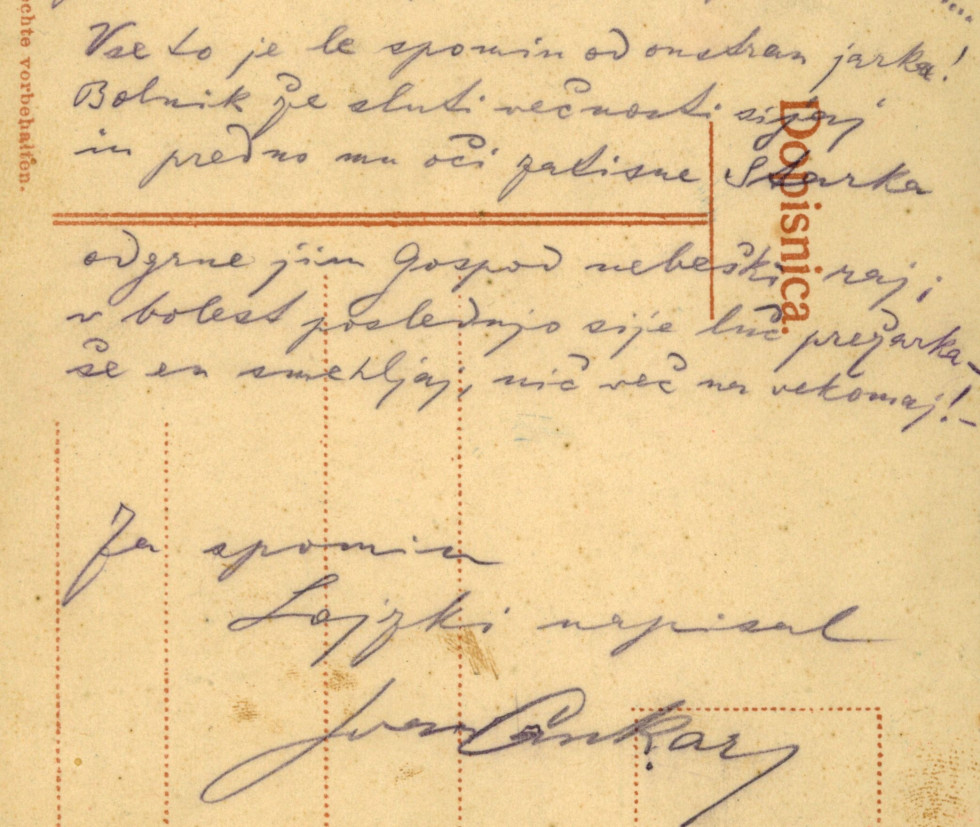

A Poem by Ivan Cankar Dedicated to Alojzija Štebi

Ten Years … Lonely Years …

Ten Years, I believe, have past; / lonely years. I wandered to desolate places, / to slopes without rest or stopping; / all that is bitter – my heart has endured. //

And what did my eyes behold as a glimpse of light in the dark? / It is you, whom I dreamt of in trepidation, / the autumn sweet light for the dead months of May, / a hundredfold return for my hundred times of pain! … //

All this is but a memory from beyond a trench! / The patient can feel the oncoming of eternity’s shine / and before the Old Lady forever shuts his eyes //

Our Lord uncovers before them heavenly paradise; / bright light shining onto the final pain - / another smile, no longer forever! //

For Lojzka from Ivan Cankar to remember me by

Placed before us is an interesting document – a postcard containing a poem and a dedication which has been preserved among the collection of personal records of Alojzija Štebi. The postcard speaks of a link between two prominent Slovenian personalities, of whom the author of the poem is one of the greatest Slovenian writers, while his »muse« is less known to the Slovenian public. She is Alojzija Štebi (1883-1956), the “forgotten half”, a female politician, editor, teacher, and a passionate fighter for the rights of women, children and the young. She is also the focus of this month’s archivalia, as is her work and her relation to the famous writer. Alojzija Štebi had known Ivan Cankar, who was seven years her senior, ever since her youth, as he was a friend of her family. Another thing they both had in common was their firm political (socialist) conviction. Alojzija’s older brother Anton and his wife Cirila Štebi Pleško were also devoted socialists. Anton was an electrical engineer, a member of the Liberation Front during the war, who died as hostage in June 1942, and Cirila died only a few months later in Auschwitz. In 1907 the bohemian writer even lived at Anton’s place for a while.

Alojzija Štebi graduated from the Ljubljana teacher training school and in 1903 landed her first job as a teacher in Tinje in Carinthia, then moved on to Tržič, Radovljica, Mavčiče and Kokra. As a devoted socialist, she was often in trouble with the authorities for having been subscribed to some politically “unsuitable” magazines, for not attending Sunday mass and for refusing to join the teachers’ organization Slomšek Union. In 1912 she left her state employment, joined the Yugoslav Social-Democratic Party and got a job at the editorial board of the daily newspaper Zarja. She also began to make public appearances at various socialist meetings and did all this at a time when circumstances were not in favour of socialists, especially female ones. Before the outbreak of the Great War she began publishing and editing a monthly magazine for women titled Ženski list and was also the editor of the magazine Tobačni delavec. In the summer of 1917 she became the editor of the social-democratic daily newspaper Naprej and the following year she also worked as the editor of Demokracija, a monthly magazine which stood for the principles of the socialist youth and the Yugoslav standpoint. Following the split within the Social-Democratic Party, Alojzija Štebi left the party and began to get involved in other projects. At the end of 1918 she took a job at the Social Care Commission of the National Government of Slovenia. In addition to all this work, she was also an editor, a lecturer, the initiator for the founding of the Children’s and Maternity Home, etc. She published educational brochures as well; in 1918 she published the brochure titled Democracy and Women and a few years later Protection of Neglected Children and Youth. Throughout this time she was active in fighting for Yugoslav women’s voting rights and for acknowledgement of their full value. She was an active member of a number of prominent Yugoslav women’s organizations – The National Women’s Union of the SHS and the Feminist Alliance of the SHS. In January 1926 she founded the Women’s Movement in Ljubljana, an organization that strove to culturally uplift women from all social strata. Organizations of this type from all over the state then merged into the Alliance of the Women’s Movement of Yugoslavia, which she herself presided over.

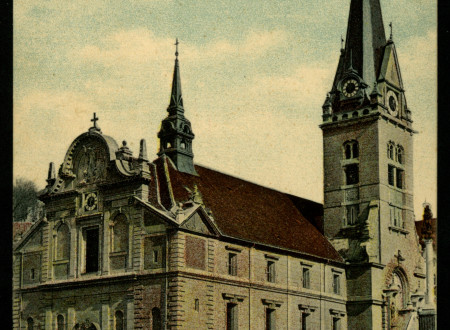

Alojzija Štebi viewed Ivan Cankar also as a role model and often corresponded with him, particularly during her years as a teacher. The postcard presented here as this month’s archivalia belongs to this time frame as well, and is believed to have been written between 1907 and 1915. Cankar wrote his sonnet on a postcard depicting the Jesuit St. James’s Parish Church in Ljubljana, situated at Levstik Square just opposite the Archives of the Republic of Slovenia. We can only guess whether this image had a deeper symbolic meaning for the two protagonists. The building, which today is home to the Archives of RS (Virant’s House), was in 1896 the place where the Yugoslav Social-Democratic Party was founded, the party that both Cankar and Štebi felt much connection with. The poem itself is deeply emotional, full of life’s bitterness and intended for a “kindred soul”, who is like the autumn light for the dead months of May. But it is not a love poem, despite the fact that the verses And what did my eyes behold as a glimpse of light in the dark? and It is you, whom I dreamt of in trepidation may indicate just that. This is why some believe that the sonnet was actually dedicated to Mica Kessler, but here the written dedication leaves no doubt as to whom the poem was intended to.

Alojzija Štebi was not only Cankar’s inspiration for this poem, he also portrayed her as a character of a socialist-oriented teacher Lojzka in his play Hlapci. In the play, Lojzka, who is loyal to the main protagonists Jerman, bows to the head teacher and to the parish priest. This caused “the real” Lojzka some discomfort and she complained to Cankar, who promised to make necessary corrections in the play, but failed to do so, because the play was censored and was not staged before 1919, a year after the writer’s death.

In her role as the editor of the newspaper Zarja, Alojzija Štebi also had to appear before the court with Ivan Cankar because of his lecture titled Slovenians and Yugoslavs, which he held in Ljubljana in April 1913. Namely, Zarja not only published the whole lecture in which Cankar expressed his idea of Slovenians joining other Yugoslav nations in a South Slavic republic, but was also the only Slovenian daily newspaper to give the lecture a positive review. Alojzija herself listened to the lecture and defended Cankar in court, but he still had to go to prison for a week (September 13-19, 1913)

In her work, Alojzija Štebi found support mostly in like-minded Angela Vode, Minka Govekar and her sister-in-law Cirila. Ema Muser describes her as »skilled journalist and editor, good speaker, simple in her public and personal appearance, kind in her personal life, steady in her conviction and independent in her thinking«. In 1940 she retired and during the war worked with the partisan movement as much as she could. After having lost her brother and his wife, she lived with distant relatives. After WWII she again found a job at the Ministry for Social Affairs and changed several jobs after that. In 1950 she retired again and worked as a part-time employee almost up until her death on August 9, 1956.

Mojca Tušar