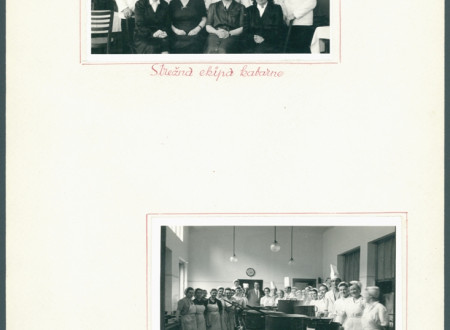

Competition Report Issued by the Trade Union Branch Office of the Hotel Union in Ljubljana for the Second Half of the Year 1951

Competition Report Issued by the Trade Union Branch Office of the Hotel Union in Ljubljana for the Second Half of the Year 1951

The document we are presenting here as this month’s archivalia was created at a time when Slovenia was still one of the republics of the former socialist Yugoslavia. While trade unions in capitalist countries have always had only one agenda and that was to pressure employers into granting their employees as many rights as possible, in socialist countries, where most of the property was owned by the state and where power was in the hands of “the people”, the tasks of trade unions have changed considerably through time. In the Soviet Union, and in the countries that modelled themselves upon the Soviet system, trade unions were originally thought of as a sort of “school of communism”; their aim was to help the communist party, that leading small-scale political force, in its effort to shape a “new man”, a spiritually rich, morally pure and physically perfect man, and their second purpose was to prepare members of the working class for the management of state administration and economy. Organizational forms of socialist trade unions changed over a course of time. The formerly split professional associations, divided by profession, vocations and political affiliation, merged into unified unions, which were organized according to the principles of the so-called democratic centralism (a system where governing bodies were elected from the ground up, and where minority was subordinated to majority) and according to industrial principle (where all employees of the same company or institution belonged to one trade union, regardless of their profession).

Founded in 1945 under the name of Unified Professional Federations of Workers and Employees of Yugoslavia, the new Yugoslav trade unions were organized in two ways; according to the principle of territory and profession. Within a company as well as within a certain territory, the most basic form of trade union organization was a branch office. Those employed in hotel trade and in catering industry were first included in the Hotel and Catering Workers Association, and after associations acquired a new name of trade unions in 1948, they became members of the Trade Union of Workers in Hotel Industry and Tourism, which operated until 1955.

Competitions were an important part of the efforts for a more successful, efficient and less costly operation of factories and institutions, and in this respect, trade unions played an especially important role. They were given a task of encouraging production growth by employing new work methods and developing “shock working” as a form of a “mass organized action”. They kept statistical data on the amount and the quality of the production lines, they gathered data on diligence, creativity and self-sacrifice of individuals and work groups, and made sure that such results were published in the printed media and heard on the radio. At first, such competitions were unplanned, usually part of some volunteer work (cleaning up of rubble, collecting old material, etc.), but even then some factories did not just count the hours of volunteer work, but made an effort to increase work efficiency. In May and November 1946 two big competitions between factories were organized. In 1947, when Yugoslavia transitioned into the period of planned economy, such competitions were taking place in all areas of work: production lines were supposed to increase production, those employed in education were expected to train and educate new skilled workers, officials in state administration were expected to perform their tasks more quickly and efficiently … In 1948, such competitions became a permanent form of work and trade unions were assigned new tasks. Special teams were visiting factories that did not meet the plan, within the companies themselves special commissions were created whose job was to reduce production costs, and, on top of that, the meeting of production plan and reduction of production costs was closely monitored by republic commissions. The best factories or institution were rewarded – they got a so-called “temporary” flag and some prize money.

The implementation of self-management in 1950 brought about big changes in the work of trade unions. During the early post-war years the unions were actively involved in rebuilding the demolished state and assisting people devastated by the war, later they also helped in constant battles to complete the planned tasks. However, when workers’ councils were created within factories and institutions, the actions of trade unions became limited to helping workers hold their elections, organize their work, and provide the needed reward for workers. Their educational role became the focus of their activities, which is nicely summed up by the Slovenian union leadership in their 1950 work report:” With the implementation of self-management, the role of union organizations changed considerably. It is now workers’ councils that are making sure the work defined in five-year plan is completed, and they do this with great sense of responsibility, whereas for trade unions their educational role is becoming more and more prominent. Union members have to be trained and educated so as to become qualified for efficient managing within their work organizations. At the same time we need to encourage and develop cultural and social life in union organizations, as well as strengthen the political and social influence of the working class in all spheres of public life.” This new direction of thought can clearly be seen also in the here presented report of the union branch office, which operated in the old and respectable crown jewel of Slovenian hotel industry – the Hotel Union in Ljubljana.

Mateja Jeraj