Italian Military Authority in the Occupied Slovenian Territory after the End of World War I

Italian Military Authority in the Occupied Slovenian Territory after the End of World War I

The closing days of the Great War were packed with sudden changes. When on the anniversary of the battle of Kobarid the Italian army launched a large-scale offensive on the Piave river, which led to the final collapse of the opposing Austro-Hungarian army, and when even Emperor Karl I failed to meet the political demands of Slavic politicians, it became clear that each must go their separate way. On October 29, 1918, Yugoslav politicians officially proclaimed the new State of Slovenians, Croats and Serbs, which united the entire Yugoslav population of the dual monarchy. The change in state authority, carried out on October 31 with the establishment of the National Government for Slovenia, was followed by replacement of authorities on regional and municipal levels as well. On the same day, the Provincial National Council in Gorizia announced that it was taking over the official business which had up to that time been carried out by the Provincial Government of Gorizia and Gradisca. National guards were also organized across the territory to ensure order and to protect the local population against the soldiers of the withdrawing Austro-Hungarian army.

Political revolution in the Austrian Littoral, i. e. in Gorizia, Trieste and Istra region, had its particularities. Namely, just days after the relations with Vienna were cut, a parallel Italian authority appeared in the region, which opted for inclusion of this territory in the Kingdom of Italy. By November 3, when Austro-Hungarian army had to admit its collapse and sign armistice in Villa Giusti near Padova, the wishes of some people came true. The armistice specifically stated the territory that Austro-Hungarian army would need to leave, and the instructions almost completely coincided with the territory demanded by the Italian government at the signing of the London Treaty in 1915. Although Yugoslav politicians anticipated that the vacant territory would be occupied also by military units of the rest of the Allied forces, this did not happen. The vacant territory remained firmly under the authority of only one Allied army – the army of the one state which had aspirations for this territory since before the start of WWI.

Already on the day of the signing of the armistice, Italian army disembarked in Trieste. In days that followed, the Italians occupied the rest of the area up to the demarcation line, agreed upon in point 3 of the armistice. Austro-Hungarian units were ordered to withdraw over the demarcation line, which caused inconvenience for some of the soldiers, who after years of fighting had to return to their coastal hometowns. Even before the occupation, the units of the 2nd mountain rifle regiment revolted against leaving for the front, and returned to Gorizia, where they swore allegiance to the new Yugoslav authority and maintained public law and order in the city for the next couple of days. With the forced departure of the regiment from Gorizia to Ljubljana, the territory west of the demarcation line was now completely under control of the Italian military authorities – General Carlo Petitti di Roreto became the governor of the political-administrative unit named by the Italians as Venezia Giulia. Transition under another, this time purely military authority, was a complete opposite from the previous Yugoslav authority, which was in place for only a couple of days.

Italian army was well familiar with the political and administrative control of the occupied territory. Already in May 1915, Italy occupied a large portion of the Gorizia and Gradisca province and established its military command over civilian population there. Experience gained at that time came in handy in 1918. Italian military authorities gained some extra manoeuvre space based on the signed armistice, which they claimed was the basis for their actions. Complaints of the local population and politicians about the fact that Italian army was occupying a territory of another state with which it had no agreement, were irrelevant. The state of SHS, proclaimed just days before, was not internationally recognized and thus de jure did not exist, while Austria-Hungary as such still existed. However, we should point out that Italian army delegated the implementation of certain provisions of the armistice also to civilians and not only to military personnel – particularly provisions concerning deportations according to article 4 of the signed armistice.

This transition under Italian military authority in the occupied territory can be studied through numerous reports of the local population, officials, politicians and other reporters, who addressed their correspondence to the National Government for Slovenia, the National Council or to the Office for the Occupied Territory in Ljubljana. We can learn that actions of the Italian military officials were basically the same throughout the entire area of the occupied territory. Each occupation was immediately followed by an order to submit all weapons and military goods of the Austro-Hungarian army and to assemble the former Austro-Hungarian soldiers at the local military command. The arrival of military units caused damage as well, as there were regular requisitions and stealing of food and property. Destruction of Yugoslav symbols was a daily occurrence and many people were punished for using Yugoslav flags or displaying Yugoslav signs, while offences such as sexual harassment, rape or attempted rape were either overlooked or considered irrelevant by military authorities. Italian was quickly introduced as the official language, although it was not understood by the majority of the population. It seemed that Italians were convinced the occupied territories would be annexed to Italy.

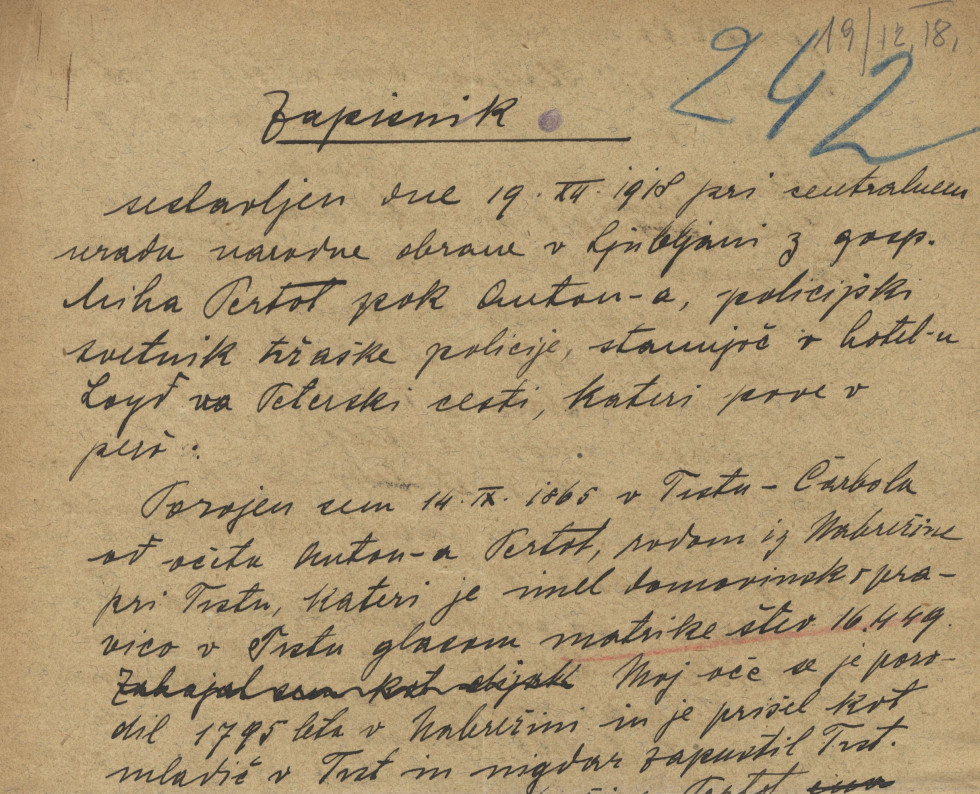

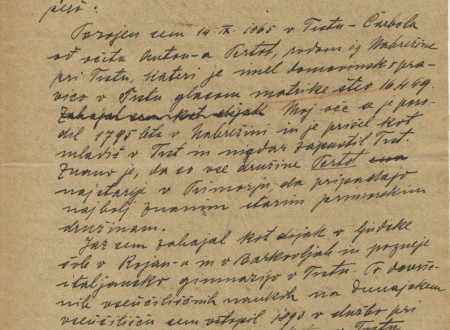

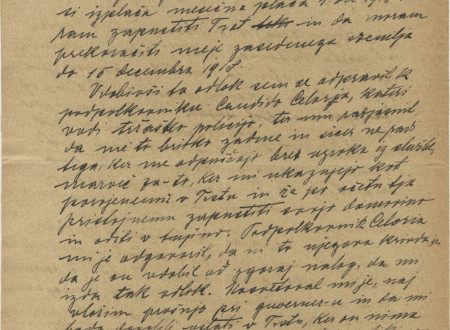

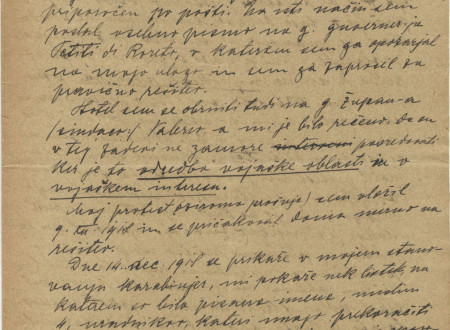

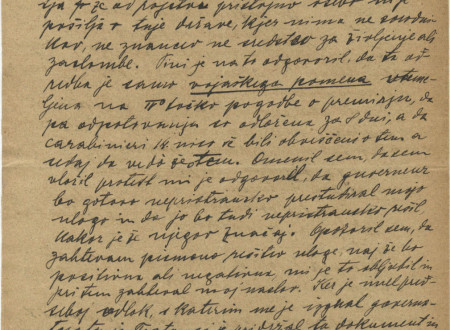

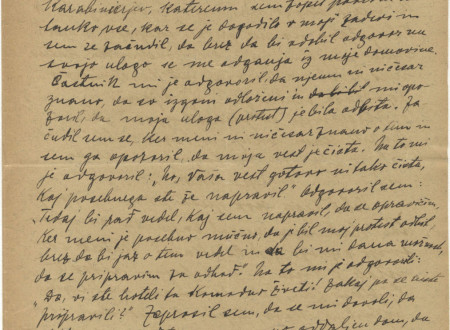

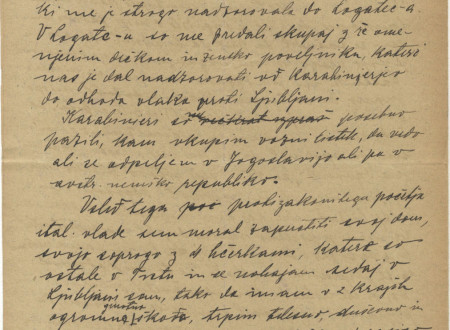

The problems faced by officials, teachers and other members of Yugoslav intelligentsia in the occupied territory are well illustrated by the minutes no. 242. Miha Pertot, a native of Trieste who was working for the Imperial Police Directorate in Trieste, was telling Fran Removš at the Office for the Occupied Territory in Ljubljana, how Italian military authorities first ordered for him to lose his job and later deported him over the demarcation line, regardless of the fact that he was working as a civil official and was educated at Italian schools. According to the decree, issued by Governor Petitti di Roreto, Miha Pertot was perceived as one of the people who were considered dangerous for the maintenance of peace in the occupied territory. Despite filing a formal complaint to revoke the decree, Pertot was after a couple of days forced to leave Trieste, accompanied by carabineers, and travel by train via Logatec to Ljubljana, while his wife and their four daughters remained in Trieste.

In addition to the original record, a copy of the certified transcript (typescript) has also been preserved. The transcript was made at Office for the Occupied Territory in Ljubljana on January 30, 1919 and is now kept by the Archives of the Republic of Slovenia among the archival records of the said office under reference code SI AS 59, box 1.

Jernej Komac