Retreat of the Yugoslav Troops South of the Demarcation Line which Divided Carinthia into Plebiscite Zone A and Zone B since July 1919

Retreat of the Yugoslav Troops South of the Demarcation Line which Divided Carinthia into Plebiscite Zone A and Zone B since July 1919

Similarly to southern Styria and its city of Maribor, Southern Carinthia with its capital city of Klagenfurt could also have been part of Slovenia today. However, the passive attitude taken in November and December of 1918 by the Slovenian National Government on the basis of its firm reliance on the Entente Powers and the Serbs, ruined any chances of that happening. Military occupation of Klagenfurt remained – despite General Maister’s initiatives to capture it – unrealized because of the supposed issues involved in food provision and because the majority of military troops were due to Bolshevik threat required to stay in industrial centres. The leading Slovenian politicians believed that the territory north of the Karavanke Mountains would be transferred to Slovenia through diplomatic negotiations. The delayed fights in Carinthia at the start of 1919 and the failed Slovenian offensive in April 1919 were followed by Austrian counter-offensive, during which Austrian Germans captured the whole of Carinthia and were even trying to make their way beyond provincial borders. Slovenian-Serbian offensive followed at the end of May and at the start of June 1919, resulting in the military troops of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians occupying the entire Slovenian ethnic territory and the city of Klagenfurt (with the exception of the Zilje Valley). But by that time it was already too late.

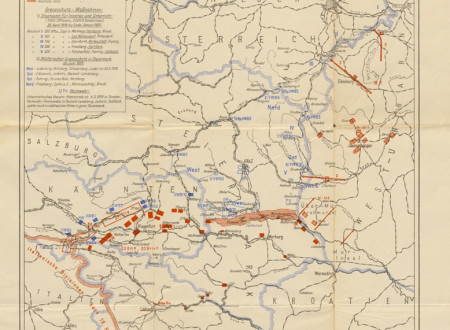

On June 21, 1919, after long and painful negotiations, the Supreme Council of the Paris Peace Conference decided that the Carinthian issue was to be solved by means of a plebiscite conducted in two zones. Zone A was to be until plebiscite occupied and managed by the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians, and Zone B was to be managed by German Austria. In accordance with this agreement, Yugoslav military troops had to retreat behind the demarcation line. On October 10, 1920, Slovenia (which at the time was part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians) lost the plebiscite in Zone A. The negative outcome was the result of inefficient Yugoslav management of the zone, but also of the pre-plebiscite brutal German-Austrian propaganda, violence, intimidation and bribery of the voters, as well as support of Social Democrats in favour of German nationalists. 41 % of Carinthinas in Zone A voted for Yugoslav kingdom, while 59 % of them voted to stay within the borders of the German Austria. In the territory where Slovenians constituted as much as 70 % of inhabitants, it was Slovenian votes that decided in favour of Austria. Austria thus gained more territory than it initially expected at the end of WWI. Namely, prior to the plebiscite the Austrians suggested not holding the plebiscite and determining the border line along the river Drava.

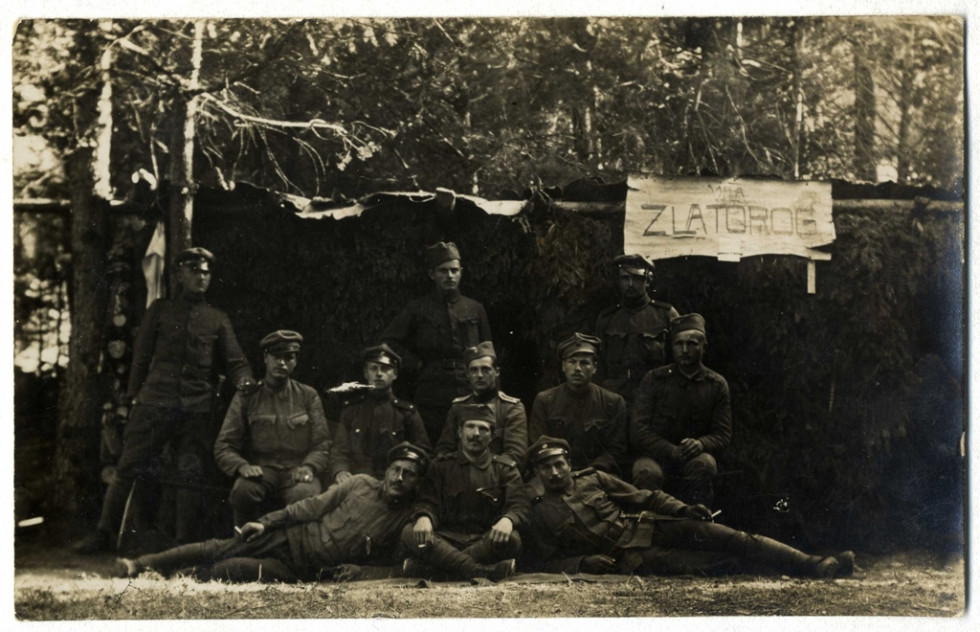

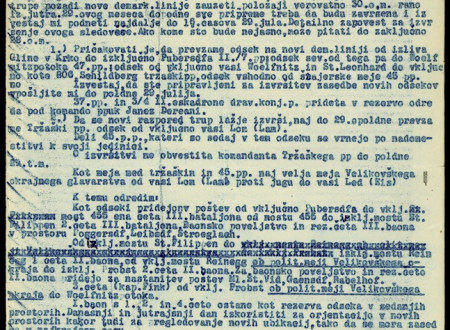

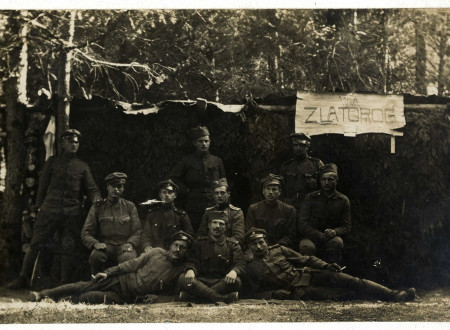

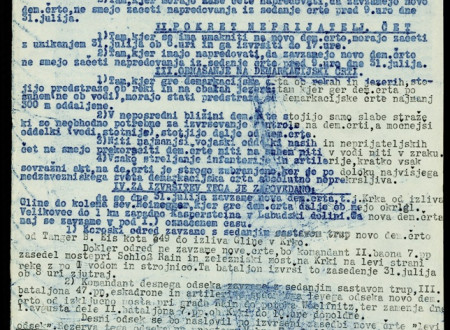

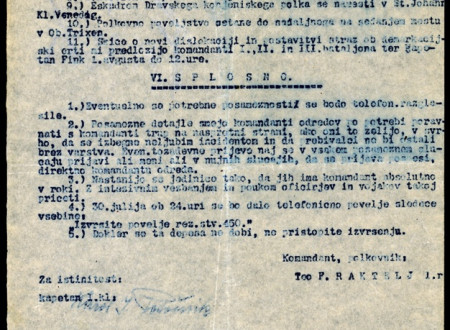

The two documents presented here – orders issued by colonel Teodor Raktelj, the commander of the 47th infantry regiment, at the end of July 1919 at the garrison in Zgornje Trušnje - refer to the troops of the 47th infantry regiment within the Carinthian detachment, located in Podjuna. They describe the preparations of Yugoslav troops for their retreat to the territories south of the demarcation line between the Zone A and Zone B. On July 31, the army of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians withdrew from the territory north of the demarcation line and left Klagenfurt as well. The two documents are fascinating also for their use of language, as one of them is written using an interesting combination of Slovene and Serbian language. The orders provide a precise description of the demarcation line and offer information on how to occupy it, when to start the retreat and from where, when to occupy a territory and where to make advancement. Also preserved from that time is a photograph (a postcard) depicting Yugoslav guards high up in the hills above Trušnje. The map depicting the positions of the Austrian and Yugoslav troops at the end of military action in Carinthia (and Styria) was printed later on.

Heavily guarded from both sides by the army and gendarmerie, demarcation line made a deep cut into the formerly unified economic and social space. Inhabitants of the Zone A were suddenly left without their natural, economic, administrative and cultural centres, to which they felt centuries-long bond. This was also one of the important factors based on which the voters at the plebiscite chose between a novelty, i. e. political union with their fellow countrymen on the other side of the Karavanke Mountains, and (as it seemed) a much more beneficial economic and administrative unity of the space which they had always been used to.

Dragan Matić