»We Shall Never Again Demand Such Help«

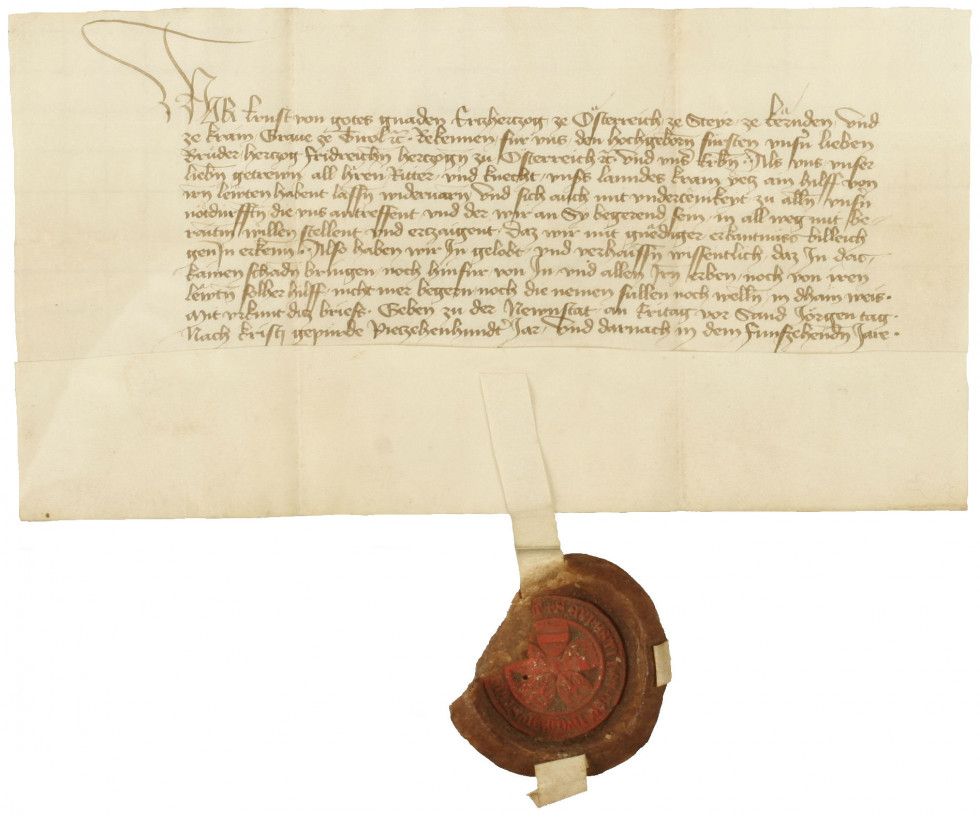

Letter of Protection Issued by Ernest the Iron for Carniolan Nobility

April 2015 marks 600 years since Ernest »the Iron«, Austrian Archduke and Carniolan Provincial Prince, issued a relatively modest deed, confirming that lords, knights and squires of Carniola allowed him to collect taxes from their subjects and in general gladly offered their help when the need arose. On his behalf as well as on behalf of his brother Frederick IV and their successors, Ernest promised that such granting of tax (help) would in no way harm Carniolan noblemen or their privileges and assured that in the future he would neither demand nor accept such help from them, from their successors or their people (subjects).

Based on reciprocal bond formed between both parties by hereditary homage, the prince was expected to protect the province, its provincial law and peace, and in return for his services received help and advice from provincial nobility and later provincial estates. This was a basic relationship between provincial prince and provincial nobility, an essential element that constituted a province as we know it from the late Middle Ages on and also the one that served as a solid foundation for the establishment and activities of provincial estates. With the accession of each new provincial prince this relationship was symbolically anchored by hereditary homage, a reciprocal oath of the prince and nobility. The former promised to respect the privileges of nobility and on this occasion confirmed them in writing, whereas the latter made a commitment to cooperate for the benefit of the province, to assure and respect provincial law and peace, to respect the established judicial norms, military defence of a province etc. In other words, the nobles formally declared “to promote the benefits of provincial princes and prevent damage”, to be loyal and obedient. Hereditary homage was a sort of contractual relation between provincial prince and provincial nobility and estates, based on loyalty and obligation. Carniolans paid hereditary homage to Ernest in 1414 and then again in 1423.

Nobility and estates were expected to help and offer advice to provincial prince when he turned to them in “times of trouble”. More often than advice (consilium, rat) the prince sought financial and military help (auxilium, hilfe) and in return promised protection (schutz und schirm). Providing advice was a duty of each individual nobleman and of the entire body of nobility. The form and the extent of such help were usually discussed at the meetings of provincial diet and “help” most commonly included providing a number of soldiers or approving tax collection. Taxes were material image of advice and help and in historical sources the term most frequently used for them is “help” (hilf, hilfgelt) and not “tax” (steuer).

Nobility’s tax exemption was formally, but not unambiguously, confirmed by provincial nobility privileges, and was in practice justified by the fact that nobility was expected to take care of the military defence of the province. Freedom from taxation held true not only for noblemen, but also for their property, estates, seigniories and subjects. Thus, regular taxation of nobility did not exist until the 16th century. Provincial prince’s emergencies and needs (called notdurfften in the document presented here) led to the approval of military help and collection of taxes, which throughout the 15th century were formally and in reality of extraordinary nature and not permanent. An early example for Carniola has been preserved to the present day. On April 23, 1415, Archduke Ernest issued a deed in Wiener Neustadt by means of which he, on behalf of himself, his brother Frederick and their successors, made a promise to lords, knights and squires of Carniola, who came to his aid, that they would not suffer damage and that he would never again demand such help from them. The document is the oldest preserved letter of protection issued to Carniolan nobility for allowing their subjects to be taxed (ain hilff von iren lewten habent lassen widervaren) and for supporting their prince whenever he needed help. It is also one of the oldest preserved letters of protection in general. Carniolan body of nobility, comprised of lords, knights and squires, allowed a non-obligatory and legally non-binding extraordinary tax to be collected. The question is whether this approval of tax collection was granted during a nobility meeting - provincial diet which might have been called especially for this purpose or whether they discussed it during one of their regular meetings, like during the session of nobility court. Evidence testifying that such provincial diet already existed is still insufficient, but we do have a solid proof of how nobility as the core of provincial estates functioned. Although isolated, this case can firmly place the beginnings of Carniolan provincial estates within time framework of stabilization of Habsburg rule in Inner Austria under Ernest the Iron.

Still, provincial diet’s approval was not a blank check for the prince to spend the collected money as he saw fit and according to his own judgement and needs. The purpose of such approval was usually very clearly specified. Approval was granted for a single occasion and was formally perceived as extraordinary. After receiving it the prince had to issue letter of protection or guarantee (Schirmbrief, Schadlosbrief) in which he expressed his gratitude to provincial nobility and assured that the approval was voluntary, granted for his sake and for the benefit of the province, that it was extraordinary and that it would in no way harm the already obtained privileges of the nobility (estates), mostly their freedom from taxation. Letter of protection was the concluding document of individual provincial diet and was, apart from the decision of provincial diet, the only legal evidence proving that the diet concluded its work successfully. In reality, such letters were of no permanent value, since the prince did not state that he would not make any such similar claims in the future, but rather assured that each approval would not damage the existing privileges and habits. He did not refer to former approvals, which means that, formally and legally, each assembly of provincial diet was a story for itself and that, theoretically, negotiations were being opened anew.

Ernest’s letter of protection to Carniolan nobility is one of the first known documents of its kind. After that there was a void which with rare interruptions lasted until the start of the 16th century. Lots of such documents were certainly destroyed, and their existence at first probably did not seem obligatory after successful completion of provincial diet. Carniolan provincial estates received their letters of protection in 1460 and 1462, and then again with Styrians and Carinthians at the 1470 interprovincial diet in Völkermarkt. The number of such deeds increased during the rule of Maximilian I (1493-1519). With over 170 examples dating up to 1782, letters of protection were a separate series of documents within the collection of deeds of Carniolan provincial estates. However, the Archives of the Republic of Slovenia did not acquire Ernest’s letter from the provincial estates archive, but rather as part of the deed collection of the 1st repertorium of the Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv in Vienna. In May 1977, this collection of deeds was returned to Ljubljana in accordance with Paris Peace Treaty (1920) and a number of international agreements.

Andrej Nared