The Slovenian Peasant Revolt of 1515

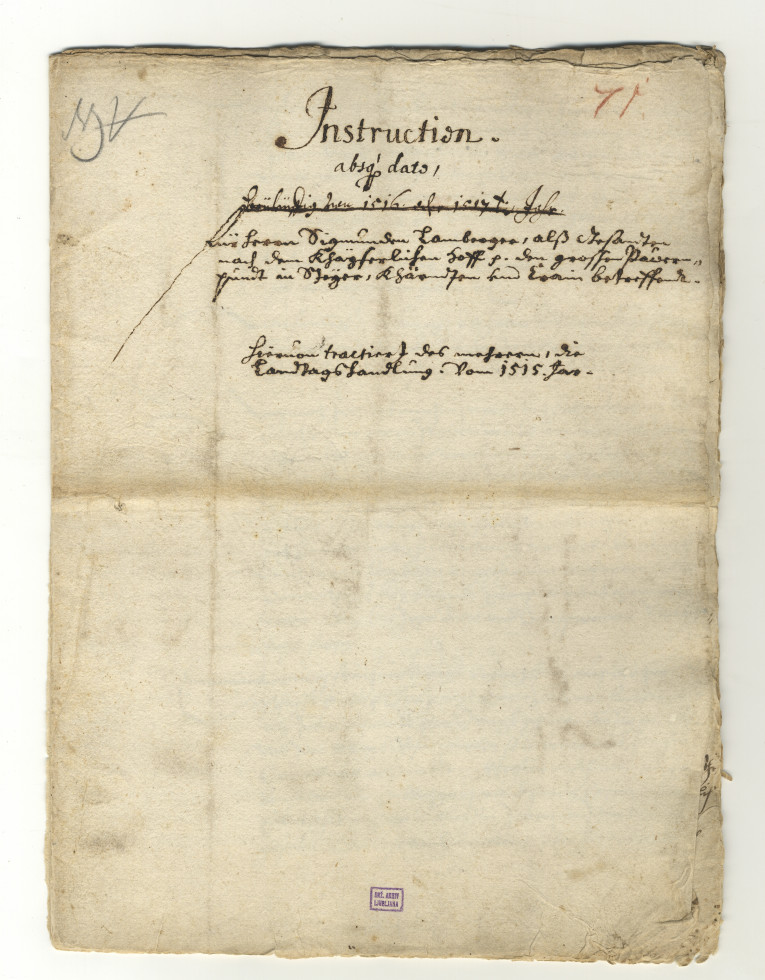

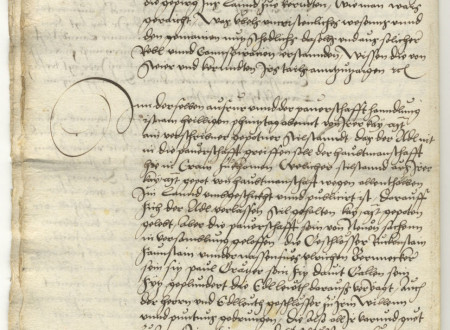

Instruction Issued by the Provincial Estates for Sigmund Lamberg of Črnelo (Rotenbüchel), Provincial Delegate to the Imperial Court

This year marks the 500th anniversary of the largest Slovenian peasant revolt which already in the sources of that time was referred to as the Slovenian Revolt (Windischer Bauernbund). Later it was characterized (somewhat unsuitably) as the “all-Slovenian revolt” since it involved the participation of a large number of Slovenian peasants. The reasons for the revolt were various and related mostly to changes in the feudal system during the transition to modern times. The most destructive blow to the peasants’ social position, however, was delivered by the long-lasting Habsburg-Venetian war (1508-1516). The increasing pressure of taxation eventually fell largely on peasants who were furthermore burdened by constant military conscriptions and also had to deal with the loss of income from the rural trade with Italian provinces and the related transportation of the goods.

Peasant uprisings on Slovenian soil modelled themselves upon the uprisings in the neighbouring lands, such as the 1511 uprising in Friuli and the 1514 uprising in Hungary. However, one should not look upon these revolts as related merely to “class hostility between feudal lords and feudal serfs”. They often had to do with the disputes between the local nobles, also common were trade-related conflicts between peasants and townspeople. Rebellious peasants were fighting for the “old rights” while placing absolute trust in kindness and justice of the emperor. Their demands to participate in the decisions regarding taxes and restriction of provincial feudal authority were also coming to the surface for the first time.

Most commonly, the serfs were upset with the lords who held provincial princely seigniories as a pledge. The latter saw their roles as an opportunity to get rich and thus continuously abused their power. The most infamous among them was Jurij Thurn (Della Torre), whose tax and other abuse brought him into conflict also with his noble neighbours and the Carniolan princely officials. The Carniolan Provincial Estates even filed several complaints against his actions to the provincial prince. In fact, almost a third of the “Augsburg libel” issued by Emperor Maximilian in April 1510 was taken up by the description of Thurn’s usurpations at the seiginiories of Kočevje, Krško, Svibno, and Klevevž.

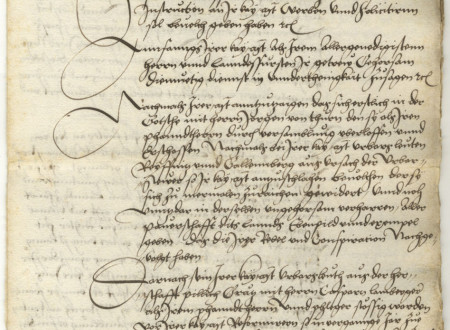

The document presented here was written after the meeting of the Carniolan nobility in Ljubljana and Kamnik, which was where most of the provincial nobles took refuge during the revolt. The instruction for Sigmund Lamberg of Črnelo, who was chosen as their delegate to the emperor Maximilian, contains valuable information about the course of the revolt. The introduction mentioned Jurij Thurn, who was killed by the peasants of Kočevje. The report moves on to describe the disobedience of the serfs from Ribnica and Gamberk, who refused to pay new taxes and so helped spread the revolt across the province. The next focus was on Polhov Gradec, where disagreement between the peasants and the pledge lord Gašper Lamberg had been an on-going issue since 1514. A number of his serfs refused to obey their lord and forced peasants who were against the revolt to join the peasants’ alliance (“Bund”). The revolt then spread to Gorenjska, to seigniories of Škofja Loka, Radovljica and Bled (with Bohinj).

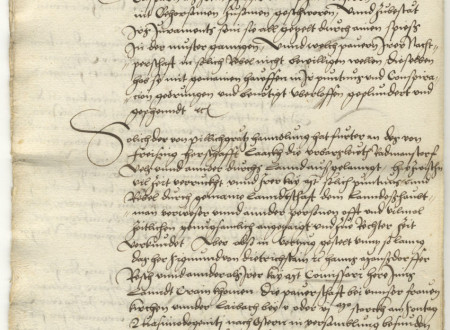

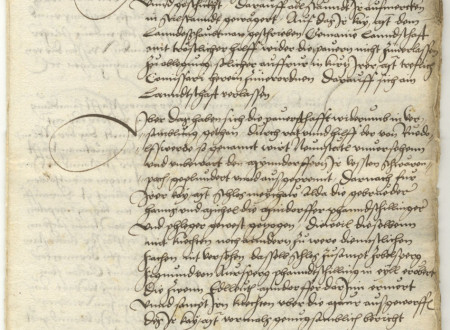

The instruction furthermore reports about the meeting of some five to six thousand peasants near Ljubljana on April 15. Princely commissioners and the Styrian provincial governor Sigmund Dietrichstein tried in vain to convince the peasants to disband their alliance and disperse peacefully. The peasants were determined to send their own delegates to the emperor. The next peasants’ meeting, at which the citizens of Novo mesto participated as well, took place near Novo mesto on May 14 and led to violence. The rebels attacked and demolished three nearby castles – particularly well reported was the fall of Mehovo Castle – and killed two noblemen, the Mindorfer brothers. The majority of the castles in Carniola and Slovenian March fell after that, and in May 1515 the revolt spread across the provincial borders into Styria, up to the river Sotla, partially over the river Drava and all the way to Graz, engulfing a large part of Carinthia as well. Especially alarming was the capture of Brežice Castle, where according to the report 50 lives were lost. Among the executed was also the hated Croation nobleman Marko of Klis, who on behalf of the Carniolan provincial governor and the vidame negotiated with the ban of Croatia for help against the rebellious peasants.

Emperor Maximilian held back military intervention of the provincial nobility for as long as he could, employing reformation commission and truce to solve the conflicts and promising to examine peasants’ complaints. However, things got out of hand and eventually the army needed to be sent in. The report states that the rebels were expecting that and blocked every passage along the river Sava. Stressing the crime of offending the emperor (laesio maiestatis) the provincial estates concluded their instruction by urging their provincial prince to take all the necessary steps and use military force to suppress the revolt, severely punish the rebels and return the confiscated property to the noblemen along with financial compensation for the damage.

According to Bogo Grafenauer the undated instruction was written after the fall of the Castle of Brežice on June 17. It was in the second half of June that rebellious peasants achieved their biggest success, which can clearly be detected from the text of the document presented here. We could perhaps place the document in the first half of July, when the army led by Jurij Herberstein inflicted a decisive defeat to the rebels at the battle of Celje, and soon after that managed also to crush the revolt in Carniola.

Vojko Pavlin