The Nagode Trial: Four Decades Later

Information of the Pubic Prosecutor's Office of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia Regarding the Initiative for Retrial Against Črtomir Nagode and Co-Defendants

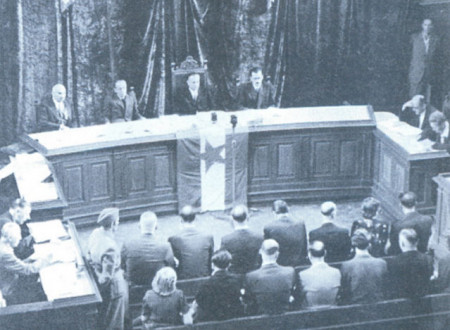

In the spring of 2015, the Archives of the Republic of Slovenia published an extensive book titled Criminal Trial Against Črtomir Nagode and Co-Defendants. The book deals with one of the most famous post-war political trials in Slovenia. Opening in the summer of 1947 before the Supreme Court of the People's Republic of Slovenia, the trial was the first of many trials staged to intimidate the existing opposition as well as any potential political adversaries, mostly those arising from the former political parties. Fifteen Slovenian intellectuals were convicted of collaboration with the movement of Draža Mihajlović during the war, and of collaboration with the spy and the »Gestapo agent« Vladimir Vauhnik, as well as with the agents of foreign (Western) intelligence with the purpose to help » the imperialistic countries« and damage the national liberation movement. After the war they were supposedly involved in organizing an armed revolt against the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia, helped by opposition politicians in Zagreb and Belgrade, Yugoslav emigration abroad (especially members of the former royal Yugoslav army), and by foreign (Western) intelligence. The defendants were accused of trying to assassin Yugoslav political leadership and of delivering intelligence reports on political and economic situation in Yugoslavia to diplomatic and other representative bodies in Western European countries. The prosecutor also accused them of smuggling people across the border, of forming a spy network throughout Slovenian territory, of inciting people against the newly established government at various meetings etc. Sentences were severe. Three of the accused were to be shot (Črtomir Nagode, Ljubo Sirc and Boris Furlan), while most of the others were sentenced to many years in prison with hard labor and loss of civil rights for two to five years. The Presidency of the Presidium of the People's Assembly of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia eventually changed death penalties for Furlan and Sirc to twenty years in prison with hard labor, while the rest of the petitions for pardon or for shortening prison sentences were mostly dismissed. One of the convicted committed suicide in prison, while most of the others were granted conditional discharge from prison between 1948 and 1954. Their further destinies differ quite a lot. Some started families and found new employment, for others the trial meant the end of their public lives. Here is where the above mentioned book ends.

The initiatives to look at the Nagode Trial from a different perspective and the demands for retrial first started to appear in the Slovenian public life in the 1980s. In her 1984 interview for the Nove revija magazine, Angela Vode described the trial as »a trial on the model of Stalin's trials«. Several intellectuals also began to draw attention to it, and the editorial board of the Nova revija magazine wanted to publish an article by one of the convicted, Ljubo Sirc, who at the time was living abroad. However, when warned by Jože Smole, the president of the Republic Conference of the Socialist Alliance of the Working People of Slovenia, that Sirc was a political emigrant, editorial board decided not to publish the article. The Committee for the Protection of the Freedom of Mind and Speech with its seat in Belgrade, whose president Kosta Čavoški was supposed to be contact with Ljubo Sirc, proposed a retrial. The proceedings were to be conducted by the lawyer Drago Demšar. The proposal was supported by the Presidency of the University Conference of the League of Socialist Youth of Slovenia. The proposal for the retrial was also discussed by the Council of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia for the Constitutional Protection. The council reached a decision that there was enough records proving that Nagode and his co-defendants were indeed trying to destroy the socio-political system in Yugoslavia, that they had contacts with foreign intelligence and political emigration, and that there were no new arguments why such retrial should take place. It was decided that the evidence material related to the activities of Nagode group should be thoroughly examined again so that the public prosecutor could provide an answer for the retrial initiators and dismiss their request. The council also believed that more thorough information regarding the less known facts about the post-war events needed to be prepared and offered to the public.

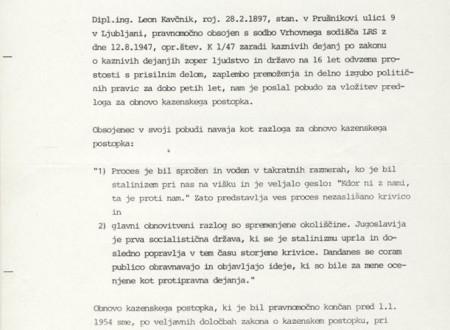

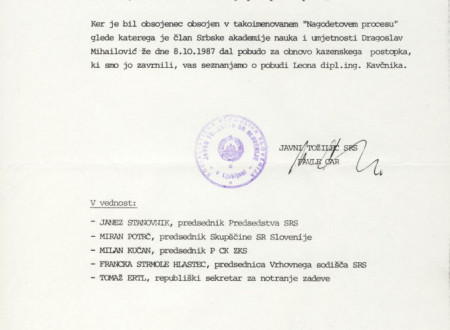

The following year, on May 18, 1988, an initiative for Nagode retrial was submitted to the Public Prosecutor's Office of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia (at the time the only authority that could make such demand) by Leon Kavčnik, who was one of the convicted ones at the original trial. This month's archivalia relates to that time. The document presented here was written by Pavle Car, the then Public Prosecutor of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia, who dismissed any chances for such retrial taking place.

Kavčnik later submitted several requests for retrial to the Public Prosecutor, one was also submitted by his fellow convict, Svatopluk Zupan. Their request was granted only at the beginning of 1991 when the Supreme Court of RS issued a decree, allowing a retrial for both of them as well as for all those convicted at the original trial. The case was sent to the court of the first instance in Ljubljana for reconsideration but before the start of the trial, the public prosecutor withdrew the 1947 indictment of the Public Prosecutor's Office of the People's Republic of Slovenia, which in 1991 led to the decision of the court to stop the criminal procedure and reverse the judgment.

The document presented here points to the fact that, despite many improvements in criminal legislation, not much has changed in the official perception of the justification of political trials in the forty years since one of the biggest political trials which so brutally violated human rights.

Mateja Jeraj, Jelka Melik