The Centenary of the Death of the Emperor Franz Joseph

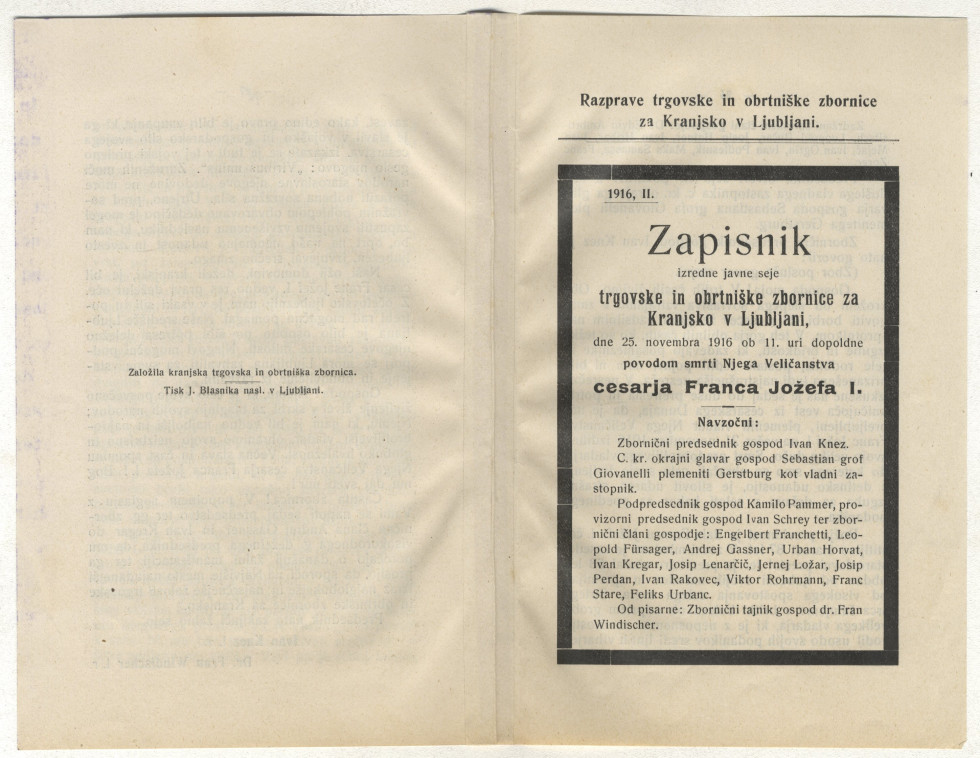

Minutes of the Mourning Session of the Chamber of Commerce and Crafts for Carniola in Ljubljana

Emperor Franz Joseph died on November 21, 1916 after having ruled for 68 years. At the time of his death, most of the his subjects, including Slovenians, could not even imagine their (national) existence outside Austro-Hungarian Empire, despite the war that had been raging for over two years and despite the decades-long conflicts among the monarchy's numerous nations.

Even at 86 years of age, the emperor was still not ready to make way for his successor. Although somewhat feeble during his last year of rule, he carried on with his Spartan work regime, waking up at half past three in the morning and ending his work at five in the afternoon. Still, one could notice that, although focused during the mornings, he would find it difficult to hold conversations during the afternoons and occasionally needed to take a nap. In November 1916 he caught pneumonia, but continued working just the same. Even on the day he died he was still listening to reports on the course of military operations and signed documents. By the evening his condition deteriorated rapidly. At half past eight the court chaplain was summoned to administer the sacrament of the anointing of the sick. Half an hour later, the old emperor died, with his daughter Maria Valerie present at his deathbed.

Carniolan Provincial Presidency was first notified about the death of the emperor a little before midnight on the same day through a telegram sent by the press office of the Ministry of Defence. The next day, November 22, the news was published in the Ljubljana daily newspapers.

Letters of condolence from offices, various societies and publicly active individuals started to pour to the address of the provincial presidency, and also to the court address in Vienna. Mourning sessions of municipal councils took place and Requiem Masses were offered for the deceased emperor in both Catholic and Protestant churches. Theatre and music events were banned until further notice and so were loud parties in pubs and in public places. Carniolans were asked to display fags in mourning and to get involved in charity work. The ban on the ringing of church bells was temporarily removed everywhere (except in the Gorizia region) and it was decided that masses commemorating the death of Franz Joseph were to be offered every year on November 21 and 22.

Letters of condolence were all written in somewhat similar manner. They usually started with expressions of deepest sympathy, followed by the listing of the emperor’s achievements, and concluded with the paying of the respect to the new emperor. Although written in the same spirit, the document that we are presenting here as this month’s archivalia, nevertheless differs a bit from the rest of such condolence letters. Carniolan Chamber of Commerce and Crafts for Carniola decided to publish the minutes of its mourning session of November 25, 1916 in the series of papers that they regularly put out. In the introduction, the speaker, the president of the chamber Ivan Knez, describes the difficult circumstances in which the country found itself. He continues by portraying the late emperor’s personality in good light and stresses a common thread to all condolence letters – namely that Franz Joseph was the nation’s ruler for as long as they can remember. There follows a brief and elated description of the economic, social and cultural progress achieved since 1848 when the late emperor came to the throne. Also mentioned are freedoms newly acquired during his reign – in politics this was the transition from absolutism to parliamentarism, in agriculture a change from tithe to free peasantry, also mentioned are changes that were made for more regulated finances and military. Special emphasis is placed on the development of industry and craft enabled by the 1868 act on chambers of crafts. According to the speaker, Carniolans also have to thank the fatherly love of their emperor for the quick reconstruction of Ljubljana after the earthquake. Finally, the speaker again expresses his gratitude to the ruler who dedicated his life to caring for the well-being of “his nations”.

In his will, Franz Joseph remembered “his nations” with only one paragraph: “To my beloved nations I would like to express my warmest thanks for the loyal love that I and the House of Habsburg received from you, both in happy times and in times of trouble. Your loyalty has helped me and strengthened my fulfilling of difficult duties as a ruler. May your patriotic sentiment continue with my successor as well.” Charles I, the new emperor, addressed “his nations” in posters that began to be printed in the Slovenian language already on November 22, 1916.

Andreja Klasinc Škofljanec