Impressions from the Exhibition on Non-Alcoholic Drinks Held in Ljubljana in 1954 and the Effort of the Slovenian Red Cross to Fight Alcoholism

Alcohol and mankind are old acquaintances. People have been growing grape vines for at least 8000 years and brewing beer since the 4th millennia BC, while distillation has been around since the Middle Ages. Still, prior to the industrial revolution, excessive drinking did not seem to pose a serious threat to society. People usually drank in moderation since alcohol was financially out of reach for most people, although there certainly were instances of drunkenness, promptly condemned by many who tried to limit the level of alcohol consumption. Before the industrial revolution, people did not drink just to get intoxicated, but also because they perceived alcohol as being food, medicine (anesthetic) and prevention against various diseases (bactericide).

Industrialization of the 18th and 19th centuries saw an increase in consumption of liquor which was mostly due to a large increase in the production of cheap liquors. Alcohol penetrated all layers of society, causing a greater demand for alcohol and turning alcoholism into a major social illness. If before alcohol was used as a medicine, it was now used as a stimulant and drinking liquor became a daily habit, particularly among the members of the lower social classes.

For a long time alcoholism was discussed only as a moral, religious or legal issue. Evil from the bottle was connected to the life of crime, prostitution and violence. Those warning about the harmful effects of alcohol were mostly Christian moralists who spread word of the effects of excessive drinking in their anti-alcohol documents. In the first half of the 19th century, Ljubljana’s town doctor Fran Lipič was the first to point out that alcohol was also a medical problem and that an alcoholic was a sick person who needed help. With this in mind, Lipič made considerable effort to establish institutions where alcoholics could be properly treated. From mid-19th century on, other professionals such as priests and doctors began to get more and more involved in fighting alcoholism, founding a number of anti-alcohol organization (such as Sveta vojska/Holy Army). At the start of the 20th century, the state as well took part in fighting the evils of alcohol consumption. Sobriety became an ideal for organizations such as Orel, Sokol, scouts and others that worked primarily with young people. Later, guidelines for anti-alcohol movements were drawn up, directed mostly towards young people, and anti- alcohol campaigns began to make their way into educational institutions.

Slovenian Red Cross included fight against alcoholism among its work priorities in 1954, when a commission was set up for this particular purpose. Sub-districts had sub-district commissions, and municipal committees had at least one person in charge of this area of work. From the very beginning the commission had set wide-reaching goals, which included both prevention (collecting statistical data on alcoholism for research, spreading anti-alcohol propaganda among the youth, ensuring larger production of non-alcoholic drinks(!), establishing home nursing service) and curative (treating of alcoholism, providing help for the families of drinkers). Today, Slovenian Red Cross continues its battle against alcoholism within its scope of activities connected to health protection.

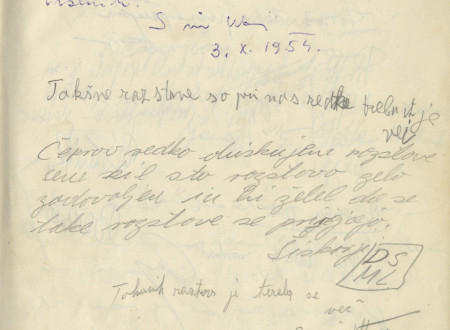

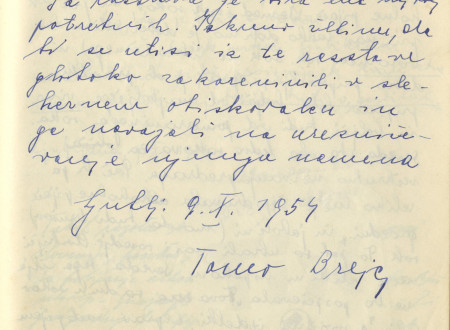

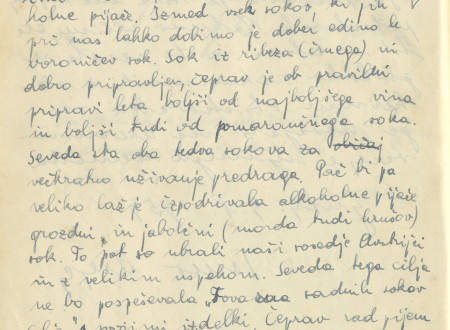

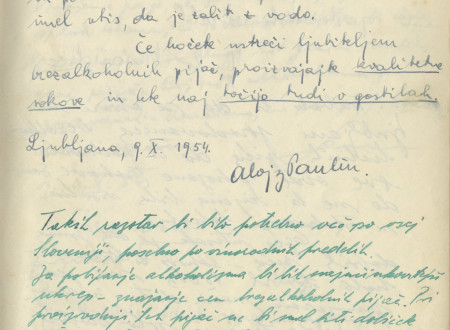

In the autumn of 1954, the Slovenian Red Cross organized an exhibition on non-alcoholic drinks. Around 30.000 people visited the exhibition and their reviews are gathered in the book that we are presenting here as this month’s archivalia. Most of the reviews were positive, encouraging the hosting of similar exhibitions, but some also drew attention to the overcharging and poor quality of non-alcoholic drinks and to the fact that it was sometimes impossible to buy them in the pubs or in the shops. The reviews include criticism such as: “As far as the idea goes, the exhibition is a well-armed force against this enemy of the whole mankind (alcoholism)”; “The arrangement is good and the idea is excellent but it will never work until the prices for non-alcoholic drinks are adjusted to those for alcoholic drinks and to our pockets”; “Congratulations for the exhibition, but if 0.5 dl of raspberry juice is 20 dinars and 0.5 dl of liquor costs the same, we shall drink liquor”; “It would be nice if such drinks could be bought cheaply!”; “Why is quality fruit only good for an exhibition and not sold to working population”; “The best weapon to eradicate alcoholism is to lower the price of non-alcoholic drinks”; “Of all the juices available here, the only good one is blueberry juice. Blackcurrant juice is not well prepared, although when prepared correctly, it is better than the best wine and also better than orange juice”; “It would be nice to have fruit juice available also in pubs”. A group of “student converts” shared the same opinion and wrote: ”Students in Ljubljana would drink less if more importance was placed on the production of non-alcoholic drinks, which around the world is widely accepted. If we have non-alcoholic drinks priced so as to suit a student’s pocket, the success is here!”.

Danijela Juričić Čargo