Election to the Constituent Assembly in 1945 – »We'll show them – never again will the old ways prevail«

August 12, 1945 (circular), November 11, 1945 (notebook of phone dispatches)

Original, typescript, one page, Serbo-Croatian (circular); a notebook of phone dispatches, manuscript, 11 pages, Slovenian

Reference code: SI AS 1589/III, Centralni komite Zveze komunistov Slovenije, šk. 6, p. e. 272/5 (okrožnica, 12. 8. 1945) in šk. 55, p. e. 1612 (zvezek, 11. 11. 1945)

»We'll show them – never again will the old ways prevail«

On November 11, eighty years ago, the first »democratic« election to the constituent assembly was held in the new Yugoslavia, or the Democratic Federative Yugoslavia, as it was officially called at the time. This election was the result of agreements reached among the Allied Powers during World War II, but post-war international political landscape had changed considerably. It was the start of the Cold War, and Yugoslavia found itself sliding more and more under the influence of the Soviet Union. Under the terms of the Tito-Šubašić wartime agreement (signed on June 16 and November 1, 1944), the new Yugoslav authorities - led and largely directed by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (CPY) – were tasked with organizing the election to the constituent assembly. This elected body would then draft a new constitution, determining the form of government to be implemented in the newly formed state. This was, of course, a historic election, as its outcome would decide whether the newly formed Yugoslavia would remain a kingdom or become a republic. From the moment the agreement on holding the election was signed, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia had been shaping its strategy around it, knowing that the election was the final obligation that the Party - as the leading force of the Yugoslav partisan movement – owed to the Allied Powers.

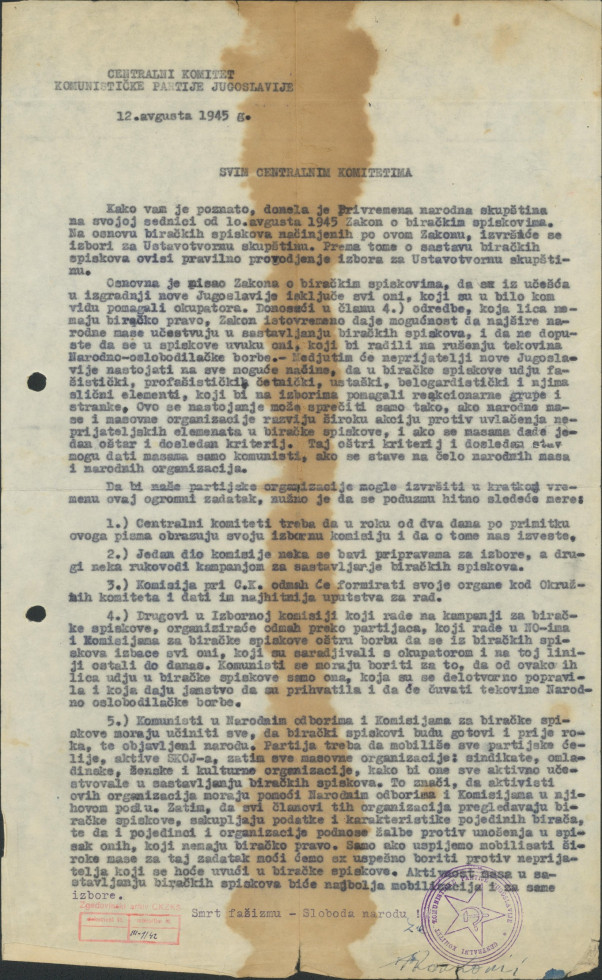

In August 1945, the third session of the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ) convened in Belgrade, taking on the role of a temporary people's assembly. The council adopted several acts, including the Act on Electoral Registers, which determined the methods of compiling electoral registers and deciding who would be eligible to vote. The act also gave the governments of the federal republics the authority to expand their electoral lists of undesirable voters. The legislation had been drafted in strict secrecy by the Ministry for Constituency, led by Edvard Kardelj, ever since April 1945. Based on this act, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia issued a circular addressed to all central committees. Dated August 12, 1945, the circular was signed by Aleksandar Ranković and is presented here as this month's archivalia. The circular emphasized that the method chosen for compiling electoral registers was crucial for the proper holding of the election. The register should, therefore, not include the names of those who had acted or might act against the achievements of the partisan movement, with particular reference to »fascist, pro-fascist, Chetniks, Ustaše, White Guards, and similar elements«. Also stressed in the circular was the role of the masses in the compilation of the electoral registers, instructing that the process be guided exclusively by the communists and that strict standard be applied to their ”cleansing”.

The Act on Electoral Registers was followed by several other acts. The voting age was lowered from 21 to 18, and women and underage participants in the partisan movement were able to vote for the first time. It was decided that voting would take place using balloting with balls, a method that was not new, as it had already been used in the »old« Yugoslavia. It was also decided that the constituent assembly would be a bicameral body, consisting of the Federal Council and the Council of Nations. A total of 348 representatives were to be elected to the former across the entire state. Slovenia, which was divided into five electoral districts, was entitled to 29 representatives. Elections to the Council of Nations were held in each federal unit. In Slovenia, same as in the other federal units, 25 representatives were elected.

The Communist Party was aware that real election required the participation of other political parties, but it did not want their influence to threaten the People's Front, which was essentially an extension of the Party itself. Alongside preparing the legislation and strengthening political unity, the Party was also creating the conditions for the elections to constituency. It manipulated the surviving pre-war parties by provoking internal disputes, which led some of them and some of their members to join the People's Front. Some, of course, joined for purely opportunistic reasons. All that the opposition and the non-communist members of the government of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia could do was stand by and helplessly watch the entire process of legislative preparation and pre-electoral campaign unfold without their involvement. In Slovenia, the opposition was weak, represented mainly by the circle around Črtomir Nagode and by certain members of the Church. Most former politicians, those who had not emigrated, were either imprisoned or placed under close surveillance of the secret police, the Department for Protection of the People. Faced with these circumstances, the opposition decided in September 1945 not to participate in such election. The most prominent non-communist members of the Yugoslav government began to gradually hand in their resignation statements; Ivan Šubašić resigned a month before the election, but the event received hardly any media coverage. The Party thus found itself in a serious dilemma, as its leaders still wanted to maintain a semblance of electoral legitimacy. They resolved this by introducing the so-called black boxes, which symbolized the king. However, the votes cast into these boxes were never counted, which means that only the candidates of the People's Front could actually be elected.

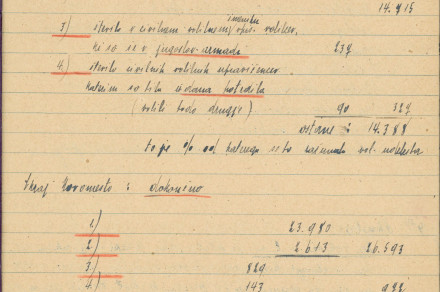

The election was held on Sunday, November 11, 1945, amid heavy rain and snow across Slovenia. However, the bad weather did not seem to deter voters, at least judging from the records in the notebooks of phone dispatches received by the Public Prosecutor's Office, which are presented here as this month's archivalia. There were several parades, ceremonially decorated carriages, singing, and flags. Undoubtedly, many people viewed the election as fear- and anxiety-inducing, given the strong presence of the secret police at polling stations; for many, taking part in the election was more an order than a choice. There were a total of 2,013 polling stations in Slovenia. In the notebook of dispatches for the district of Novo Mesto there is a record for the village of Toplice near Novo mesto, which testifies to the atmosphere: »The whole village is on its feet. There is a radio opposite the polling stations, informing the people about the course of the election throughout the state.« The records highlighted the examples such as the following: »In Ajdovec (Novo mesto) a former Home Guard member, who was deceived, stated before the polling station: I was a member of the Home Guard, because I was misled. Even though I do not deserve the right to vote, I can vote. I know who I am voting for – I will vote for Tito!«. In their elation, people even spat or threw black boxes on the floor. Among the dispatches, the most frequent reports describe elated voters who were friendly towards the new government, but there are also some reports on those who opposed it. The dispatch for the district of Grosuplje reads as follows: “In Žalna we noticed that the families of bega (i. e. White Guard supports) come to the polling station together and the black box is filling up.« Additional agitators were sent to some of the less frequented polling stations. In several cases, the Department for the Protection of the People had to intervene. There are testimonies of the balls (votes) from the black boxes being placed into the red ones, or of black boxes not being provided at all. Those who refused to vote for the People's Front risked losing their job. Voter turnout in Slovenia was around 92 percent, with roughly 85 percent voting for the People's Front (the lowest percentage in Yugoslavia). Officially, the »opposition« or the »black box« celebrated victory in two Slovenian districts – in Dolnja Lendava and Gornja Radgona, but due to voting geometry the candidates of the People's Front were ultimately elected, despite losing the election.

A month before the election, the British Foreign Office, in a special analysis, compared this election to the one held before 1941 – they identified its »Balkan characteristics« and concluded that the only truly fair and free election in Yugoslavia had been the one held in 1920.

Mojca Tušar

- SI AS 1589/III, Centralni komite Zveze komunistov Slovenije, šk. 55, p. e. 1612 (Election to constituent assembly).

- Šteiner, Martin: »Prve demokratične« volitve v Jugoslaviji 11. 11. 1945. In: Zgodovinski časopis 51, 1997, no. 1, pp. 103−105.

- Vodušek Starič, Jera: Prevzem oblasti 1944−1946. Ljubljana: Cankarjeva založba, 1992, pp. 308−369.