»The Lowest Paid Provincial Archivist in Austria« asks the Carniolan Provincial Diet for a Salary Increase

Ljubljana, January 14, 1894, January 14, 1895

Original, six pages

Reference code: SI AS 38, Deželni zbor in odbor za Kranjsko, šk. 1227, št. 1.462, 12.390

Anton Koblar (1854-1928) | Author Štefan Rovšek/dLib

In November 2025, the Archives of the Republic of Slovenia is celebrating the 80th anniversary of its founding. It was originally established as the Central State Archives of Slovenia by a decree of the National Government of Slovenia, adopted on October 31 and enacted on November 7, 1945. Due to administrative and political changes, its name was changed several times, most recently in 1990, yet its mission remained the same, even gradually expanding over decades. Throughout the eight decades of existence, and despite the issues that have become synonymous with archives (inadequate and insufficient facilities, staff shortages, lack of financial resources and insufficient support from decision-makers), the Archives has evolved into a modern state archival institution. Today, it celebrates its jubilee in its brand-new building on Poljanska Street. Although we still need to face many challenges, these are modest compared to those faced by the Slovenian state archives at its inception or even earlier, when it was still part of the Carniolan Provincial Museum and later the National Museum in Ljubljana.

The Carniolan Provincial Museum, founded in 1821, was from the very start also involved in collecting deeds, manuscripts, records, genealogies, noble diplomas, various correspondence, and similar materials - in other words, it collected archival material, which was organized into a special collection. At first, the archival department of the museum was a bit neglected due to staff and space limitations. This created opportunity for the Carniolan Historical Society, which in the mid-19th century became very active in its care for archival material. The society’s archive held a good number of documents and was open for research use. Its members were also active in recording manorial, town, market town, and parish archives. The society’s initiative to merge its own archive with that of the museum and so create a proper provincial archive in Carniola with the help of the provincial authorities, was unsuccessful. After the society was dissolved, its archive was transferred to the Provincial Museum in 1885.

After the new Rudolfinum Provincial Museum building was completed, the museum archive and the archival collections of the dissolved Carniolan Historical Society were added, in the second half of the 1880s, to the existing archives of the Estates and the Vicedom, all housed in shared premises. By joining under the roof of the newly constructed Carniolan Provincial Museum the materials that had up to that point been collected and kept by the Provincial Committee, museum and the historical society, the main conditions for the founding of the provincial archive were finally met. The archive acquired sufficient and suitable space, but the persistent problem of insufficient funds to employ a qualified archivist on a permanent basis remained unsolved. After years of construction and relocations of the collections and after the death of the very diligent curator Karl Dežman, the momentum to formally establish an independent provincial archive or at least a special organizational unit within the museum with its own employee, was apparently lost. As a result, a provincial archive was never established, even though the 1894 reorganization of the museum and the state funds allocated for it provided a great opportunity for such a step. Although the terms “provincial arhive” or “provincial archivist” appeared in some of the discussions of the Carniolan Provincial Diet and in historical writings of that time, in legal and formal terms no such institution existed. Up until 1918, Carniola remained the only land of the former Austrian Empire that did not have its own independent archival institution. The official head of the archive was the museum curator; in the spring of 1889 this position was taken over by Alfonz Müllner.

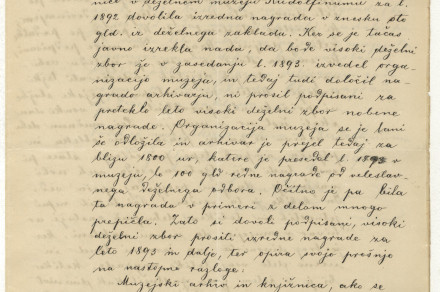

This month’s archivalia takes us back to the final decade of the 19th century, when the post of the “provincial” archivist was occupied by Anton Koblar (1854-1928) - a priest, historian, editor and politician. In 1889, the Provincial Committee appointed him the chaplain at the forced-labour institution, and a year later they entrusted him with the organization of the archive at the Carniolan Provincial Museum. Koblar created a collection of deeds, arranged them, compiled their regests and transcriptions, and devoted some of his time also to the arranging of the materials obtained from the monasteries in Kostanjevica and Stična, from the Seigniory of Dol, and from the Estate’s archive. As he was already employed at the forced-labour institution, he only received a yearly reward of 100 gulden for his work at the archive, although this sum was increased upon his special request several times. Koblar complained that his work was not valued enough and was engaged in frequent disputes with Müllner. The latter used to take documents that he needed for his articles into his office without previously notifying the archivist of doing so. In general, Müllner seems to be a conflictive person, but Koblar was no angel either. Their correspondence with the Provincial Diet and the Provincial Committee, preserved in the “archival fascicle” (SI AS 38/IX/5/4) bears witness of their playful bickering.

Two requests (which were also complaints) that Koblar addressed to the Carniolan Provincial Diet provide some insight into the character of Koblar and into the unresolved status of his role as an archivist. Earlier, on December 30, 1893, he sent two letters to the Provincial Committee, addressing himself as the “head of the provincial archive in Rudolfinum”. The first letter contained a balance sheet for archive’s expenses and a request for an advance to cover future costs. In early January 1894, the Provincial Committee approved the submitted balance sheet and instructed the “provincial treasury” to transfer additional funds. Koblar also requested a special reward for his work at the archive and library but soon received a reply stating that no special rewards had been approved for 1893, and therefore the committee could not grant his request. However, Koblar was informed that he could submit his request directly to the Provincial Diet …

“The head of the museum archive in Rudolfinum”, or more precisely “the archivist” Koblar, did not hesitate to act, and on January 14, 1894, he wrote to the Provincial Diet, asking for a 100-gulden reward for the years 1893 and 1894. He reminded the Diet that, in the spring of 1892, he had already been granted a reward of 100 gulden for his »arrangement and management of the archive and library”. He explained that he made no special request for the year 1893, because the matter was expected to be resolved with the planned reorganization of the museum, which, however, never took place. Therefore, for 1,800 hours of his work in 1893, he had received only the regular reward of 100 gulden, which was not nearly enough. He justified his request for a special reward in vivid terms, as can be seen in the document reproduced for the purpose of this month’s archivalia. Let us just take a look at a few excerpts: “The gruelling work at the archive does not merely cover one’s clothes and lungs in dust but also strains one’s eyes when reading old scripts. The early loss of eyesight is the inevitable fate of every archivist. /…/ It is true, that the author of this letter likes working at the archive and that it was his love of archival work that inspired him to do it. But to spend one’s days compiling dull catalogues for others, and one’s nights working on what one needs for oneself – this is no pleasure for anyone, and no one would do it for such meagre pay.” For these reasons, Koblar asked the Provincial Diet to grant him a special reward of 300 gulden for the year 1983 (he had already received a regular reward of 100 gulden), and to award him a continuing annual payment of 400 gulden from the “provincial treasury” – to remain in effect until the planned reorganization of the museum was completed and for as long as the Diet remained satisfied with his work.

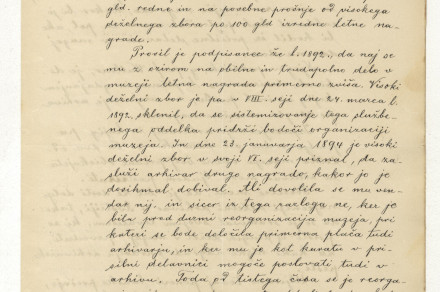

His request was partially successful, as in mid-February 1894, following the decision of the Provincial Diet, he was paid 200 gulden, 100 gulden as a special reward for each of the years 1893 and 1894. Less than a year later, the story repeated itself. On December 21, 1894, he wrote to the Provincial Committee, explaining that although he had received a special reward of 100 gulden granted by the Provincial Diet for the current year, he had not yet received the regular reward of the same amount. He asked for the payment and requested that “the honourable Provincial Committee grants him at least 300 gulden annually for his work at the museum, without the need for burdensome petitions to the honourable Provincial Diet, since the rewards so far and the ways in which he had to apply for them, were not proportionate to those received by other museum employees /…/ and insufficient for the painstaking and very extensive work of the museum’s archivist and librarian”. On December 27, the Provincial Committee confirmed payment of the regular reward and advised Kobler to take up the matter of the permanent increase of his regular pay to 300 gulden with the Provincial Diet, as that was the body competent for such decisions.

On January 14, 1895, Koblar once again wrote to the Provincial Diet. In his letter, he stated that he had been working in the archive and library since February 21, 1890, receiving an annual regular reward of 100 gulden, with additional special reward of 100 gulden granted by the Provincial Diet upon his special request. He had already asked for the increase of his reward many times, but the Provincial Diet always kept using reorganization of the museum as an excuse. And even though on January 23, 1894, it had acknowledged that Kobler in his role as the archivist deserved a higher reward for his work, he was still not granted one. In his capacity as a chaplain at the forced-labour facility he was also receiving a reduced priest’s salary (700 gulden), precisely because he was supposed to also be paid for his work as the archivist at the Provincial Museum. “Yet the undesigned is by no means obligated to sacrifice all his free time, his clothes and his health to a dusty and unheated archive”, he wrote, and for such a modest payment as well. Koblar argued that his predecessor Wallner had been receiving 40 gulden per month for his work at the archive, without having to deal with the library at all. And it was precisely the lending out of archival materials and books that was increasingly taking up more of his time. “The petitioner believes that he has long enough been the lowest paid provincial archivist in Austria, to the point that he feels ashamed to tell his colleagues who come to visit the museum from other lands how insufficiently paid he is for his work at the archive”. Finally, he repeated his “last year’s request”, asking the Diet to grant him a regular annual reward of 400 gulden.

In the second half of the 1890s, Koblar began to gradually withdraw from his duties (in 1896 he was elected member of the state parliament) and was ready to hand over his post to a successor. After 1900, he served as parish priest and dean in Kranj until his death. At the end of 1899, Müllner recommended Franc Komatar to the Provincial Committee as Koblar’s replacement, but Komatar didn’t join the archive until 1903, and even then only for a year and a half, leaving at the end of 1904 for a post of a professor at the grammar school in Kranj. Komatar was also appointed as a collaborator of the archival section of the Central Commission for the Research and Preservation of Art and Historical Monuments, and as the conservator for Carniola on the Archival Council in Vienna. He, however, had similar “reservations” as his predecessor. His swift departure from the museum was partly due to his resentment over at the fact that, following Müllner’s departure in mid-1903, the former museum caretaker and taxidermist Ferdinand Schulz, a man Komatar regarded as “a dismissed gendarmerie sergeant”, “who has no academic training; who cannot even write or speak German, much less Slovenian” had been temporarily appointed to the position of a curator. Among the records of the Slovenian Museum Society (SI AS 619) is a draft of Komatar’s letter from November 16, 1904, announcing to the Provincial Committee his resignation as the provincial archivist. In addition, he complained that “my pay is so small that I am ashamed to mention it if anyone asks me to; I would earn more helping Schulz stuff animals”.

Andrej Nared

- SI AS 38, Deželni zbor in odbor za Kranjsko, box 1227, 1228.

- SI AS 619, Slovensko muzejsko društvo, box 7, SI AS 619/I/6/12.

- Nared, Andrej: Arhivska dediščina Deželnega in Narodnega muzeja v Ljubljani. In: Argo 64, 2021, no. 2, pp. 140−151.

- Nared, Andrej: Od arhivske zbirke Kranjskega deželnega muzeja do Arhiva Republike Slovenije. In: Narodni muzej Slovenije: 200 let (ed. Tomaž Lazar idr.). Ljubljana: Narodni muzej Slovenije, 2021, pp. 291−312.

- Šlebinger, Janko: Koblar, Anton (1854–1928). Slovenska biografija. Slovenska akademija znanosti in umetnosti, Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU, 2013.