Archival Legacy of Karel Smolle

1986-2009

Original, copy, draft; 4 documents, 20 pages

Reference code: SI AS 2235, Smolle Karel, šk. 15, 28, 37, 97

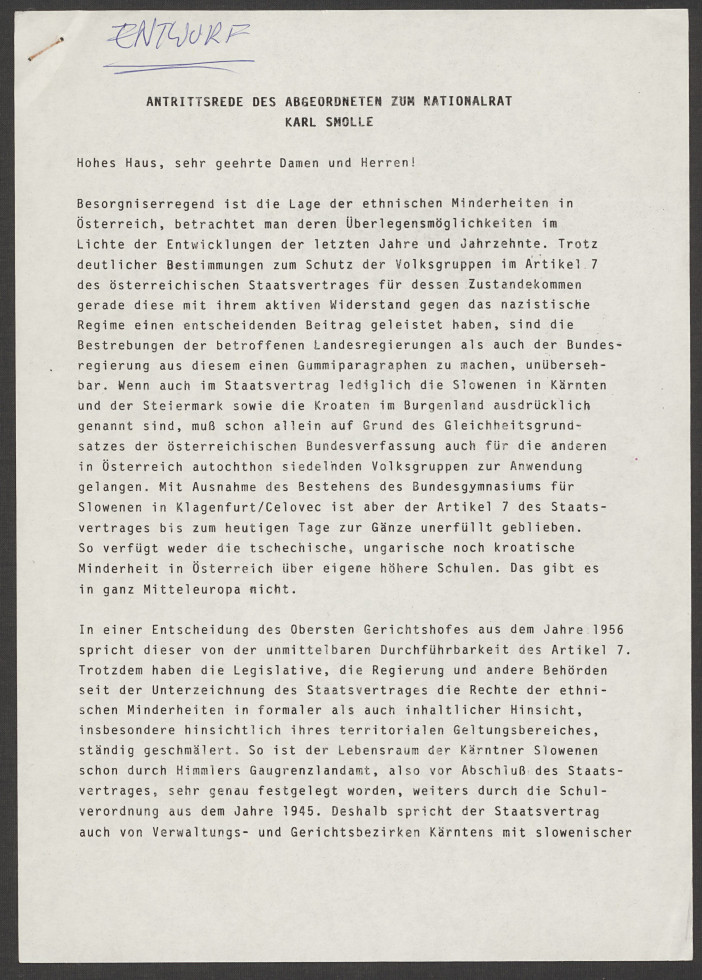

Inaugural speech of the member of the Austrian Parliament Karel Smolle, draft, no date (believed to be from 1986) . | Author Arhiv Republike Slovenije

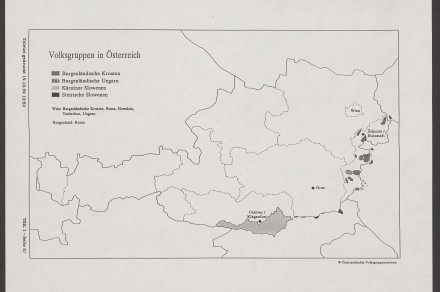

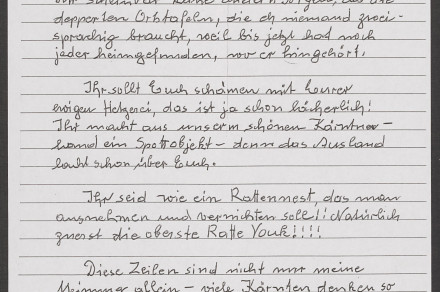

After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and the political and diplomatic bargaining that followed it, part of Slovenian population ended up as an ethnic minority living outside the Slovenian and Yugoslav borders. The border with the Republic of Austria remained unchanged even after World War II, leaving a large part of the southern Carinthia within the Austrian state, despite the development of the events and the Yugoslav and Slovenian adamant demands against it. Diplomacy tried to secure the rights of these Carinthian Slovenes through the Austrian State Treaty of 1955, but the social climate in Austrian Carinthia had historically been rather hostile to Slovenians, and some of the provisions of the treaty still remain to be fully implemented to this very day. Despite criticism that members of the Slovenian minority in Austrian Carinthia have been indecisive and not active enough in assuring the treaty’s full implementation, there are a few exceptional individuals that stand out in this regard.

Karel Smolle was born in Borovlje (Ferlach) in 1944. He spent his childhood with his mother and his sisters initially at his uncle’s place at the vicarage in Šmarjetna v Rožu (Sankt Margareten in Rosental), where he was able to learn Slovenian well in a completely Slovenian environment. According to his own words, his life at the vicarage gave him a privileged position, as it was a place where information about the events in a wider area flowed daily, and his uncle, in whom Smolle found a role model of a proud, socially conscious man and spiritual leader, owned a well-stocked library, especially with Slovenian literature.

He became actively involved in advocating for the rights of Carinthian Slovenians already during his time at the Plešivec (Tanzenberg) grammar school, where there was a strong group of Slovenian students that published a newspaper “Kres”. When he began attending the Slovenian Grammar School, where no such student organization existed, he was one of the founding members of the Carinthian Student Association. During that period of his life, he also began writing poetry, which he then published under the pseudonym Miško Maček, and in 1965 he published a collection of poems titled Ujeti krik.

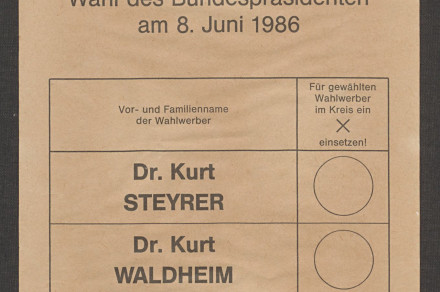

Despite his literary success, Smolle dedicated himself to his political work advocating for the Slovenian minority in Carinthia. Having finished his studies of law, he opened his translation office in Vienna, which enabled him to retain complete independence from any influences that everyday politics and different political movements might have on his personal beliefs. In 1986, he was elected to the Austrian parliament as a candidate for the political party Alternativna lista (Alternative Liste Österreich), predecessor of the Green Party. In his parliamentary role, he devoted most of his effort to strengthen the role of Austria’s national communities, particularly Carinthian Slovenians. They managed to ensure the broadcasting of radio and television shows not only for Slovenians, but also for Croats in Burgenland, they established a bilingual federal commercial academy, they made sure that members of minorities were included in obtaining compensations for the victims of Nazism, etc. He established and maintained contacts with members of the southern Tyrolean minority in Italy, and in 1984, he and his colleagues founded a Slovenian Centre, which in time grew into the Austrian Centre for Ethnic Groups. Smolle regularly relied on this centre when searching for ideas and guidelines needed for his parliamentary work. He was also a co-founder of a very active Slovenian Economic Union. He was elected to the Austrian parliament for the second time on the Liberal Forum’s party list. The extensive net of contacts he built during his time as a member of the parliament proved highly beneficial when Slovenia embarked on its path of independence and sought international recognition. With the consent of the Austrian government, he became the founder and the head of the Slovenian representative body in Vienna, which later grew into the Slovenian embassy in Austria’s capital.

Throughout his work, he accumulated a lot of archival material, which, after careful consideration, he decided to hand over to the Archives of the Republic of Slovenia. Although much of it, like most of the private fonds - and as he himself acknowledges in his article “Koroški Slovenci in avstrijske politične stranke” – was rather disorganized and thus difficult to navigate. However, in this “pile of paper”, as he describes it himself, one can still find interesting records that shed light on the events taking place among the population of a national minority. In addition to material, accumulated through his personal interests and duties tied to his various roles in the public life, a number of the preserved documents also illuminate Carinthian reality in the past and today. Such documents focus mainly on their struggle and efforts to secure rights and resolve issues of the Slovenian minority, as well as describe the development of the events taking place on the Yugoslav/Slovenian and Austrian side of the border before, during, and after Slovenia’s gaining of its independence.

As is the case with every private fonds, archival fonds of Karel Smolle has its own characteristics and peculiarities. Acquisition and processing of private archival records can at times be a bit stressful for archivists, especially when creators are handing over their collections themselves and do not sort and appraise the material before transferring it to archival institution. When arranging and describing such records, archivists inevitably come across every piece of paper, including documents and notes that may contain family, personal and political secrets, which may give them an uncomfortable feeling of intruding on private matters or of revealing actions that may have unfavourable effect on the public image of the individual. However, time often softens certain judgements, and the creator that is handing over his collection of documents can also in their donation agreement specify the time limits within which his transferred records or part of such records remain unavailable for visitors of archival reading room.

There is another interesting detail that needs to be mentioned in connection with Smolle’s archival records. Being used to reading working documents on paper, he was accustomed to also print out his e-mails. Since his wife, Draga, was a general practitioner and there was always a lot of paper generated in her office, Smolle, in the manner of a responsible and ecologically conscious individual, printed a lot of his e-mails on the back side of no longer used medical records of his wife’s patients. Today, when legally protected personal data included in archival records need to be anonymized, especially medical information about individuals, which is additionally protected by a separate law, any usage of such material in archival reading room gets particularly complicated. Besides personal and medical data of his wife’s patients, Smolle’s archival records also include personal data of third persons, such as for example of his family members. Mr. Smolle as a donor did not specify any particular conditions regarding the keeping and availability of his archival records.

Despite these challenges and the fact that, due to the nature of his work and engagements, his donated material contains many copies or just fragments of documents, the Archives of the Republic of Slovenia is very honoured and grateful to Karel Smolle for deciding, as a conscientious Slovene, to transfer his archival legacy to archival institution in his homeland.

The written legacy of Karel Smolle consists of 111 archival boxes and covers a period between the years 1924 and 2024. Presented here as this month’s archivalia are some of the interesting documents from his archival legacy.

Alenka Kačičnik Gabrič

- Smolle, Karel: Koroški Slovenci in avstrijske politične stranke. In: Moritsch, Andreas (ed.), Bahovec, Tina (ed.): Koroški Slovenci 1900–2000: bilanca 20. stoletja. Celovec - Ljubljana - Dunaj: Mohorjeva, 2000/2001, pp. 137–154.

- Zerzer, Janko (ed.): Valentin Inzko: glasnik sožitja: 1923–2002: zbornik prispevkov in spominov. Celovec: Mohorjeva, 2015.