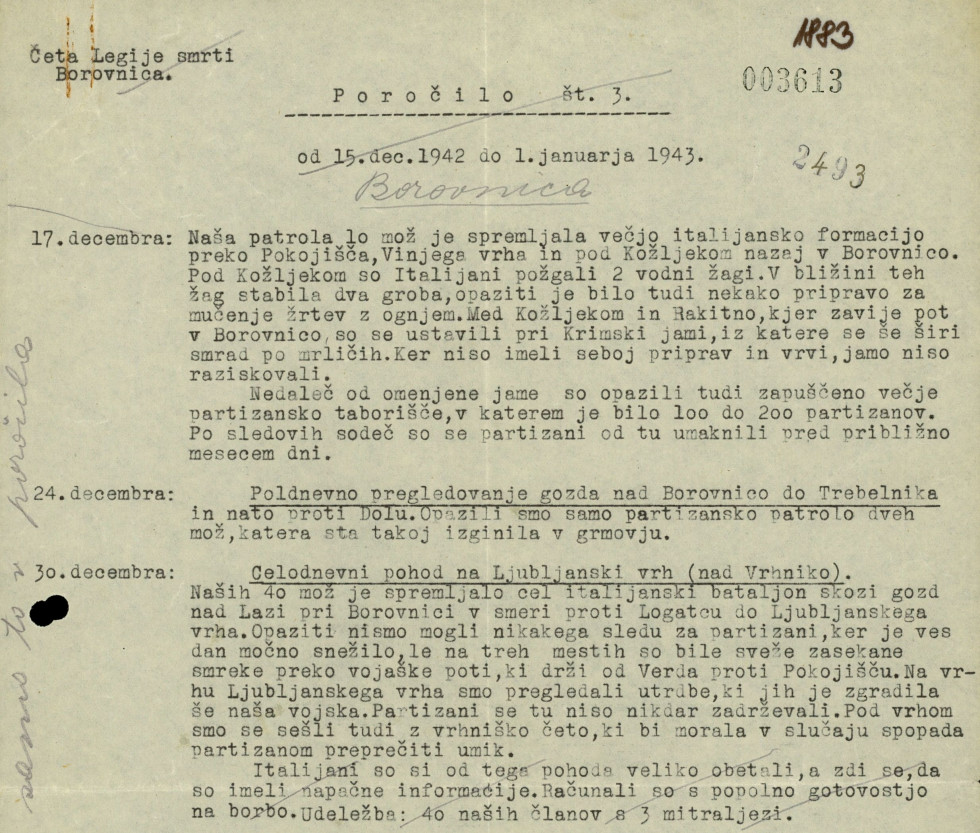

The Report of the Village Guard in Borovnica for the Period Between December 15, 1942 and January 1, 1943

Brezovica, January 2, 1943

Original, typescript, 2 pages

Reference code: SI AS 1931, Republiški sekretariat za notranje zadeve SRS, Podfond Ostanki meščanskih strank, ZA 600-20, Arhiv dr. Šmajda, box 930

Extract from the report of the village guard in Borovnica for the period between December 15, 1942 and January 1, 1943, Brezovica, January 2, 1943. | Author Arhiv Republike Slovenije

Village guards operated from the summer of 1942 until the capitulation of Italy in September 1943. They were widespread mostly in the surrounding areas of Ljubljana and in Inner Carniola and were formed out of the growing tensions existing between the supporters of the Liberation Front and its opponents. At the time, the partisans were losing some of the support among the rural population, who began to notice instances of the partisans’ revolutionary violence and experienced first-hand the Italian retaliations for the partisan actions. They were also strongly influenced by the anti-Communist attitude of the Slovenian People’s Party (SPP). Village guards usually consisted of the inhabitants of a single place and their mission was to protect their village and its immediate surroundings. Italian authorities were initially distrustful of the village guards, but with time began to support such way of fighting the partisans, partly also because of the intervention of the local Slovenian priests and politicians. At the start of August 1942, General Mario Robotti, commander of the Italian army in the Province of Ljubljana, named village guards Milizia volontaria anticomunista (Anti-Communist Volunteer Militia), and by the end of that year the founding of such militia units was authorized also by the authorities in Rome. However, Italians did not allow any autonomy to such village guards. Their stations were subordinated to the command of larger Italian units and any merging of local village guards was not allowed. They were mostly assigned poor equipment, outdated weapons, and only exceptionally they received heavy weapons. Organization work was done mostly by the so-called village guards committee in Ljubljana, which included some of the leading personalities of the Slovenian People’s Party, among them also Albin Šmajd.

The report of the village guard in Borovnica shows the kinds of operations the local guards were involved in, their equipment and arms, it discloses how they managed their finances and food supply and explains their relations with the local villagers and with the Italian occupying troops. Report no. 3 covers the time between December 15, 1942 and January 1, 1943, and was signed by the commander of the Borovnica guard Ludvik Kolman (1905-1992) under a pseudonym Ludovico Borovšek. He was a lawyer by profession, who before the war was employed at the Banovina Labour Inspection, but managed to pass his officer’s exam during his field training exercise. Before the war, he was drafted and witnessed the collapse of the Yugoslav army in Varaždin, from where he ran away from the Germans and found refuge in Ljubljana. In September 1942, he joined the village guard in Borovnica and became its commander. He chose to remain in Borovnica station together with his team even after Italy capitulated. He managed to convince the Germans to let them keep their weapons and he pushed for the inclusion of the village guard in the Slovenian Home Guard. In May 1944, following his dispute with a German commander stationed in Borovnica, Kolman was arrested by the Germans and he spent a year in prison in Ljubljana. When he was released just before the end of the war, he moved to Šentjošt and then to Carinthia. He managed to avoid being returned to his homeland. In 1950, after years of living in Austrian camps, he and his family arrived to the United States of America and settled down in Waukegan, Illinois. As a Slovenian lawyer, he was unable to find suitable work in America. He got a job as a factory worker, and was an active member of the Slovenian organization called Tabor, operating as its president for several years. He wrote a number of articles for the magazine Tabor as well as for some other American magazines.

Kolman’s report also includes information about the killings of Janez Demšar and Anton (Tone) Zalar-Žan, two prominent communists from Borovnica involved in the national liberation movement in the area. Demšar (1910-1942), a carpenter by profession, had been a member of the Communist Party of Slovenia (CPS) since 1941. Zalar (1904-1942), a locksmith and a railway worker, was a pre-war revolutionary (a member of the Communist Party of Slovenia since 1933) and a syndicalist, who on account of his work for the communist party had already been imprisoned and persecuted even before the war. In July 1941, he was arrested by the Italians and sent to prison in the Ljubljana Šempeter barracks, from where he soon managed to escape. He joined the Borovnica partisan unit and was appointed the political commissar. After the failed march to Lower Carniola and in order to get away from the bitter cold winter, Zalar’s unit withdrew to the valley, and Zalar built himself an earth cabin above Borovnica. When at the start of December 1941 the partisans again started to gather in the surrounding area of the village Kožljek, Zalar joined them and became the commissar of the newly formed Kožljek unit. In 1942, he was appointed the secretary of the Borovnica district committee of the Communist Party of Slovenia. In September that same year, during the great Italian offensive, which lasted from July to November 1942, Zalar and another two members of the district committee, Janez Demšar and Viktor Kirn, built a bunker in a place above Brezovica, from where they carried out their political work across the surrounding areas of Borovnica. They visited partisan families, organized confidants of the Liberation Front, printed radio news, organized food supply for the partisans and kept contacts with the local partisan units. On December 14, 1942, members of the village guard from Borovnica discovered the bunker; Zalar was killed by a bomb, Demšar, who was wounded in the shooting, committed suicide, and Kirn was captured.

This report of the village guard in Borovnica for the period between December 15, 1942 and January 1, 1943 was just one of the many such documents collected by the lawyer and politician of the Slovenian People’s Party Albin Šmajd. Since not a lot of anti-communist archival records have been preserved, documents of this kind are especially valuable.

Mateja Jeraj

- SI AS 1487, CK KPS, box 25, description unit 2614, Medvojno poročilo OK KPS Vrhnika (the end of December 1942).

- SI AS 1546, Zbirka življenjepisov vidnejših komunistov in drugih osebnosti, box 9 and 58 (folders with bibliographies).

- Maček, Janko: Oče, ti si na vrsti. In memoriam Ludvik Kolman. In: Zaveza, no. 8, pp. 58–60.

- Mlakar, Boris: Milizia volontaria anticomunista. In: Enciklopedija Slovenije, Vol 7. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 1993, pp. 144–145.

- Mlakar, Boris: Vaške straže. In: Enciklopedija Slovenije, Vol. 14. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 2000, pp. 153–154.

- Mlakar, Boris: Začetki oboroženih oddelkov protirevolucionarnega tabora v Ljubljanski pokrajini. In: Jasna Fischer et al. (ed.): Slovenska novejša zgodovina: od programa Zedinjena Slovenija do mednarodnega priznanja Republike Slovenije: 1848–1992, 1. del. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga; Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2005, pp. 656–661.

- Tominšek Čehulić, Tadeja, Šorn, Mojca, Rendla, Marta, Dobaja, Dunja: Smrtne žrtve med prebivalstvom na območju Republike Slovenije med drugo svetovno vojno in neposredno po njej. Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 1997–.

- Vidovič Miklavčič, Anka: Slovenski železničarji pod italijansko okupacijo v Ljubljanski pokrajini 1941–1943. Ljubljana: Inštitut za zgodovino delavskega gibanja; Železniško gospodarstvo Ljubljana, 1980.