»Where Do All Our Nation’s Daughters Go?«

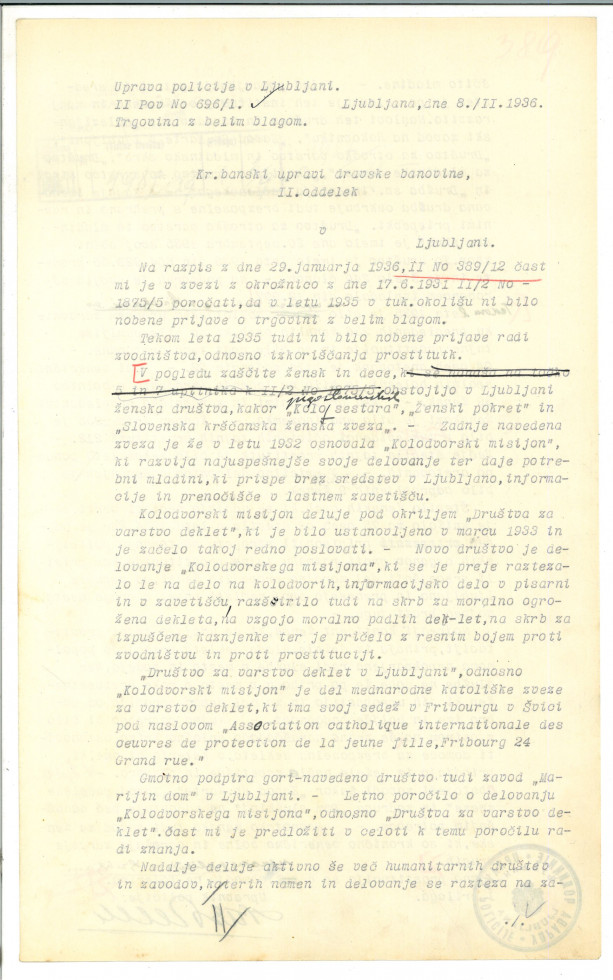

Ljubljana, January 28, 1936, February 8, 1936

Original, transcript, paper, 6 pages

Reference code: SI AS 68, Kraljevska banska uprava Dravske banovine, Upravni oddelek, policijske zadeve 13-10, description unit 303/1938

The first page of the report of the Police Administration in Ljubljana to the Royal Banking Administration of Drava Banovina. | Author Arhiv Republike Slovenije

Human Trafficking in the Drava Banovina

Human trafficking has due to its profitability always been part of a social sphere. Its criminal nature, however, has throughout time continually generated efforts to prevent it. In December 1920, the League of Nations adopted a resolution on preventing human trafficking and asked its members how they coped with the issue.

The Police Directorate in Ljubljana replied with an extensive description of their activities, punishments for those involved, and even suggestions of how they could increase their effectiveness in uncovering illegal transactions.

According to their reply, any enabling of prostitution or recruitment of people into prostitution was punishable by three to six months prison sentence. Seduction of an innocent victim led to one to five years in prison with hard labour. If the victim was younger than 14 years of age or had been taken by force, prison sentence could be extended to ten years and even longer than that, if the victim suffered medical consequences.

Hotels, lodging houses and inns were closely supervised, and women, caught in suspicious company of men or other women, were questioned. During the interrogations, the authorities tried to establish what was the purpose of their coming to Ljubljana and what they intended to do there. The authorities could help them find suitable work or deport them back to their home municipality and notify their relatives.

Foreigners, who wished to employ girls as servants, waitresses or home teachers, were also checked. The Police Directorate was in contact with the Ladies of Ljubljana Committee and St. Martha’s Institute, whose job was to take care of the unemployed girls. Girls, who were caught engaging in morally questionable activities but still wished to return to honest work, were usually directed to these two institutions. The incorrigible ones were sent to court and then to correctional homes or a compulsory workshop. They kept a record on the captured prostitutes, the circumstances that had led them to such life, their potential diseases and changes of residence.

The police also supervised employment agencies, immigration agencies and charity organizations. They paid special attention to women, who wished to go abroad; no travel documents were issued to them without the prior consent of their parents or the court. In accordance with the provincial government regulations of July 1919, the police, together with railway police and border commissioners, checked the passports and other travel documents of passengers. By the end of March 1921, only one case was recorded, when a Bosnian merchant was accused of trying to persuade thirteen girls to travel with him. He went to court but was then released due to the lack of substantial evidence. Later they found out that he had been charged with similar offences even prior to his arrest in Ljubljana.

The Police Directorate was of the opinion that such activities would definitely have to be monitored by the central authorities in Belgrade, which would then provide local authorities with information on suspicious persons. Houses of tolerance (brothels) would also need to be subject of special supervision. Although the brothel in Ljubljana was closed down in 1919 and the girls working there, most of whom were of Hungarian descent, were deported to their homeland, Ljubljana still had a lot of clandestine prostitution.

The Directorate recommended establishing special committees in the cities and villages of the districts from which many people travelled abroad, believing that such committees would be more successful than the police in detecting any unusual happenings. Cities should open homes for unemployed girls, who were most at risk of falling into the hands of the criminals. Such homes should employ ladies willing to make sacrifices to offer good advice and help the girls through troubled times.

District governors were obligated to send yearly reports on human trafficking and prostitution, but those were mostly unspecific. The safety of travelling women and children was ensured by the police and the moral education and protection of children was in the capable hands of various charity societies, such as the Branch Office of the Yugoslav Sisters Group and the Catholic Ladies Charity Society. The recommendations of the authorities to improve the situation were summarized by the newspaper Slovenec, which also suggested that the police force in Ljubljana, following the example of some other countries, should include among their ranks some suitable women, who would deal with underage children and be present during the interrogation of girls, arrested by the police for the first time. In general, the article depicts less optimistic picture than the official reports … “A number of people from the countryside complain that our girls, who move to the cities to find work, are getting lost …”

The yearly report of the police in Ljubljana also shows a rise in the number of women, who were arrested when offering illegal services and had sexually transmitted diseases. In the following years, that number dropped, but this could be attributed to the fact that, faced with increased pressure, they preferred to move to the south, where the measures taken against them were less strict. There were also reports on procuring, when a female victim was lured away from home under the pretext of getting married, but was then forced into prostitution. The female owner of the café was suspected of selling her employees.

In 1927, a man was suspected of recruiting young girls in an employment agency and sending them to a café owner and innkeeper in Novska to work as maids, but once they got there a totally different faith awaited them. He was arrested and sentenced to four months of prison.

In May 1930, a man from Bosnia began to appear in various pubs in Jesenice. He was known to pay for the drinks and invite waitresses to go with him to Belgium, where he would find them good jobs. He managed to persuade one to go with him to Ljubljana. A woman from Maribor also came forward, claiming that the man took her money and her passport in order to get her a visa for Belgium. He was believed to have been persuading another girl. He promised them all to marry them, even though he had already been married and had a child. He was sentenced to a year in prison for his deception, but was acquitted of the suspicion of having committed a crime against public morality.

In 1932, Slovenian Christian Women’s Union founded a Railway Station Mission, which offered various information to the passengers at the railway station. Due to the ever-increasing needs the Society for the Protection of Girls was established in 1933, which took over the Railway Station Mission and was at the same time also charged with taking care of “the morally threatened girls, for education of morally fallen girls, for the released female convicts, and for the start of serious fight against procuring and prostitution”. The society was part of the international Catholic union for the protection of girls, which had its seat in Switzerland. One or two members of the society regularly went to the railway station and awaited the arrival of every train so that they could talk to the young people and girls in particular and offer them help, should they need it. Their office was near the station and their shelter called Mary’s Home offered cheap or free accommodation for the girls who came to Ljubljana looking for work. Unemployed maids could also find cheap accommodation at St. Martha’s Institute, at the Maids’ Home, at the job agency in Wolf Street, and at the Servants Association Institute.

Reports show the versatility of the work done by these “railway station missionaries”. They provided travellers with some basic information about the arrivals and departures of trains and gave them directions to various offices. They helped travellers, who felt dizzy, with drops or a glass of cognac, dressed the wounds of injured travellers and helped women who were about to give birth to reach the hospital or took them from the hospital. They offered help to people with mental health conditions, helped carrying the invalids and guided the deaf and speech disabled. They advised foreigners, helped in searches for the missing persons, provided protection for the girls, accompanied travellers to a specific office, bus or a job agency, offered support for legal protection of women, provided information about available employments, etc. They always had an aspirin, a nappy or some cotton balls, if these were needed. They called for the taxi or an ambulance and they provided food for the hungry. In addition to offering concrete help to the arriving young girls, the missionaries also warned them about potential dangers and looked after the children. They worked from seven o’ clock in the morning to half past ten at night, when the last train arrived at the station. They cooperated with the police and were in constant contact with their headquarters in Switzerland, as well as with similar societies in other parts of the country. Since the number of young people moving from the countryside to the cities was increasing, such railway station missions began operating in Maribor and Celje as well.

The Archives of the Republic of Slovenia also keeps some of the records describing the operations of the mission during 1941 and 1946 in our Railway Station Mission Records (SI AS 1758).

In 1936, the police force in Ljubljana employed its first female employee Danica Melihar Lovrečič, who dealt with under-age children, prostitutes, murders (mostly infanticides), sodomy and sexually transmitted diseases.

Olga Pivk

- SI AS 68, Kraljevska banska uprava Dravske banovine, Upravni oddelek, policijske zadeve 13-10, description unit. 303/1938.

- Kod hodijo naše ljudske hčere? In: Slovenec, vol. 56, 2. 8. 1928, no. 174, p. 3.