Tito: Tihomir, Ian, Kamilo, Filip, Jozef or Josip, That Is the Question

Documents on the Search for Tito's Identity

History knows of stories and personalities who never cease to captivate our imagination and excite us. Whether awakened by memories, publicists or other serious scientific work, such personalities instantly come to life whenever even the slightest fragment of archival material concerning them appears. The magazine Newsweek Srbija recently revived the story of searching for Tito’s real identity. Based on the Gestapo files that had up to the publishing of the article been closed, as claimed by the magazine, the article describes the agonizing and persistent search of German authorities for the “phantom” leader of Yugoslav partisans. According to Ivo and Slavko Goldstein, the two authors of Tito’s political biography, Tito was known to change his identities as often as he changed his clothes. In our era of unimagined technological development and rapid spread of information it is easy to forget that conspiracy, which the communists seemed to excel in even before WWII, was a hard nut to crack for the German intelligence. German intelligence services were supposedly trying to acquire information on Tito’s identity and his appearance not only in Yugoslavia, but all over Europe as well, spying on such data from Paris to Prague and the Soviet Union. Kamilo Horvatin, Tihomir Tomić, Filip Filipović, Russian spy Nikolaj Lebedev, Slovenian Jew Niderle, Karlo Bros, Ivan Brozović, Jozef Broz Vaclaj or Toša Tišmar? None of these identities turned out to be true.

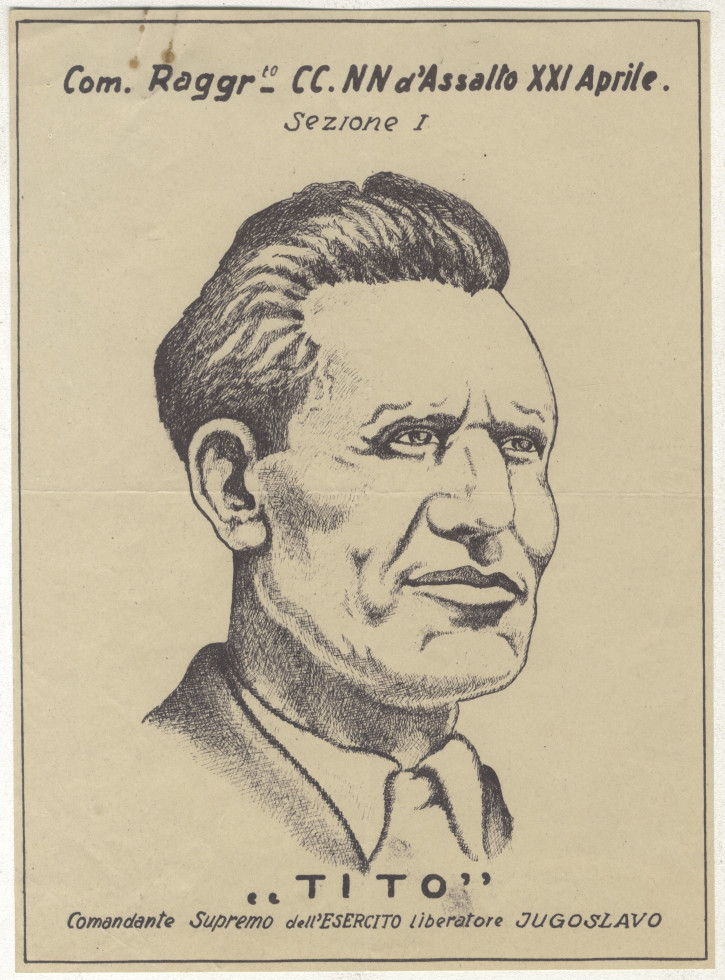

One of the earliest German documents on Tito that was published by the aforementioned Newsweek Srbija dates from September 1942. It describes the testimonies on Tito given by the German prisoners-of-war that were exchanged for the wounded partisans in Livno. A short summary of what was in that document can also be found in Italian documents that are now kept at the Archives of RS, indicating that German intelligence did not just possessively hold on to their discoveries, but were for the sake of reaching their goal willing to share them with the other Axis powers. The Archives of RS preserves these documents as circular letters written on a soft transparent paper that can be found among the records of the fonds SI AS 1783, Karabinjerska postaja Borovnica/Italian Gendarmerie Station in Borovnica, in boxes 1 (description unit 13) and 3 (description unit 33). A well-known drawn portrait of Tito is included in the fonds SI AS 1842, Zbirke gradiva raznih enot italijanske vojske /Collection of various Italian army records, box 1, description unit 7. These documents shed light on how Ivan Brozović painfully turned into Josip Broz – Tito.

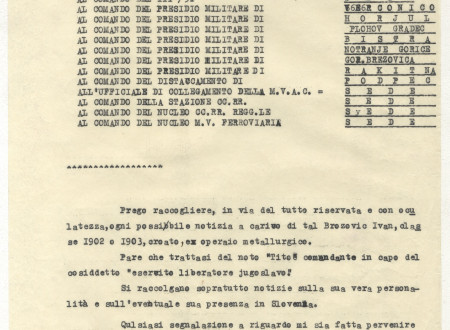

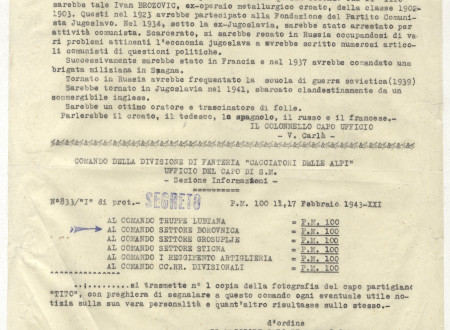

Italian units apparently “allowed” themselves to become familiar with Tito’s true identity from their stronger German ally. The aforementioned Italian documents reveal that Italian police and military command in Slovenia from that moment on had a mission to discover whether Tito, as was “known” then, was in fact in Slovenia or not. In December 1942, when Italian police knew quite a lot about what they perceived to be the leading Slovenian “communists”, such as Josip Rus, Edvard Kocbek and even Edvard Kardelj (SI AS 1783, Karabinjerska postaja Borovnica, box 6, description unit 73), they still had no substantial data on Tito. In February 1943, Italian 2nd Army mistakenly offered to its subordinate units as a real Tito a much younger Ivan Brozović. The latter was supposed to be born in 1902 or 1903 and was supposed to be a former metallurgist and communist since 1923. He was believed to be arrested for his communist activities in 1934 by the then Yugoslav authorities. After serving his time he was believed to leave for the Soviet Union where he was included in various political matters concerning the economy in his homeland. Supposedly he even wrote about such issues and published his articles. After that he was believed to go to France and even lead the “police brigade” in Spain during the Spanish civil war in 1937. After his return to the Soviet Union, he was believed to attend military school and in 1941 return to Yugoslavia – in utmost secrecy – on a British submarine. He was believed to be an excellent spokesman, who spoke Croatian, German, Spanish, Russian or French language to address his audience and fill them with enthusiasm.

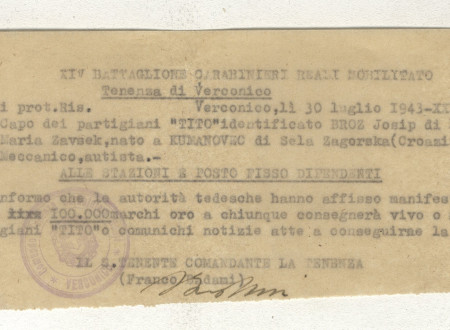

However, by the end of July 1943, the Italian carabineers – even those in Vrhnika – received a notice from their superior unit. The notice was once again based on the German findings about the real Tito and the circular letter finally introduced them to Josip Broz Tito. According to their data, Tito was born on March 6, 1892 in Kumanovec (not Kumrovec) in Croatia. He was a metallurgist and a driver (not a locksmith). They also found out that the German commander-in-chief in Serbia offered a reward of the then 100,000 German marks for Tito.

Here we have to ask ourselves a question of how such data could be useful to Italian forces from that moment on. The last time the Italian units and Tito were facing each other was at the battle of Neretva, where Tito’s legendary command “Prozor noćas mora pasti” (“Prozor must fall tonight”) was meant exactly for them. Not long after that they clashed again at the battle of Sutjeska, after which in the summer of 1943 Tito withdrew from Monte Negro to western Bosnia and away from Italian positions. When Italian authorities finally got to the real Broz, western allied forces were well positioned in Sicily, the Italian military morale was falling uncontrollably, and Mussolini and the Italian high command increasingly often ordered withdrawal of their Balkan units to the Adriatic coast and called for the defence of their homeland against the western allied forces. September 8, 1943 was not far.

We know today that discussions about Tito’s identity did not end once the war was over; they have just acquired new dimensions.

Tadeja Tominšek Čehulić