The Project "Triglav Lift System"

The project “Triglav Lift Systems” was among the most ambitious, yet unfortunately never realized, Slovenian tourist projects. Its aim was to make the Slovenian highland, which usually was accessible only to experienced mountaineers, closer and more approachable to the general public and so facilitate the development of tourism in the surrounding areas.

Even before the WW1, the Triglav mountain range was a well visited destination in the summer, but somewhat less tempting for ski tourers during winter season due to avalanche hazards. Skiing became more of a possibility in the spring, once the danger of avalanches was over. In the spring the region was being visited by admirers of unspoiled nature and skiers making ski trails in slightly melted spring snow.

Established in 1921, the “Turistovski klub Skala/Tourist Club Skala” saw an opportunity for a great ski run in this part of the mountains. On April 25, 1927, the club organized the first ski race from Kredarica to the Krma valley, which the following year was named the Triglav Downhill and took place once a year until the 1950s. By the end of that decade another, even more ambitious project, began to take shape. In 1959, Slovenian sports and tourist workers gathered in Bled and decided to build an alpine centre. Choosing between two possibilities - “Velo polje” and “Triglav Lift System” – they finally opted for the latter after carrying out extensive research and study.

The role of the project developer, both in terms of technical realization and financial responsibility, was assigned to the Institute for the Construction of Sports Centres in the Triglav Mountain Range with its seat in Bled. In September 1963, the institute prepared its work report and a Proposition to include the project of Triglav Lift System in the seven-year plan of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia, stating several obvious reasons why the project should be carried out. At such high altitude the skiing season could last for as long as six months, starting in December and ending at the end of May. The Triglav Glacier, which today has all but disappeared, could provide a year-around skiing. The region’s position at tripoint of Austria, Italy and Slovenia and good transport connections were expected to attract foreign guests. There was no need to build any large accommodation facilities since the existing capacities in Bled, Mojstrana, Jesenice, Radovljica and Kranjska Gora would be of help. And finally, by means of such project the Triglav mountain range would be well visited also by tourist in summertime.

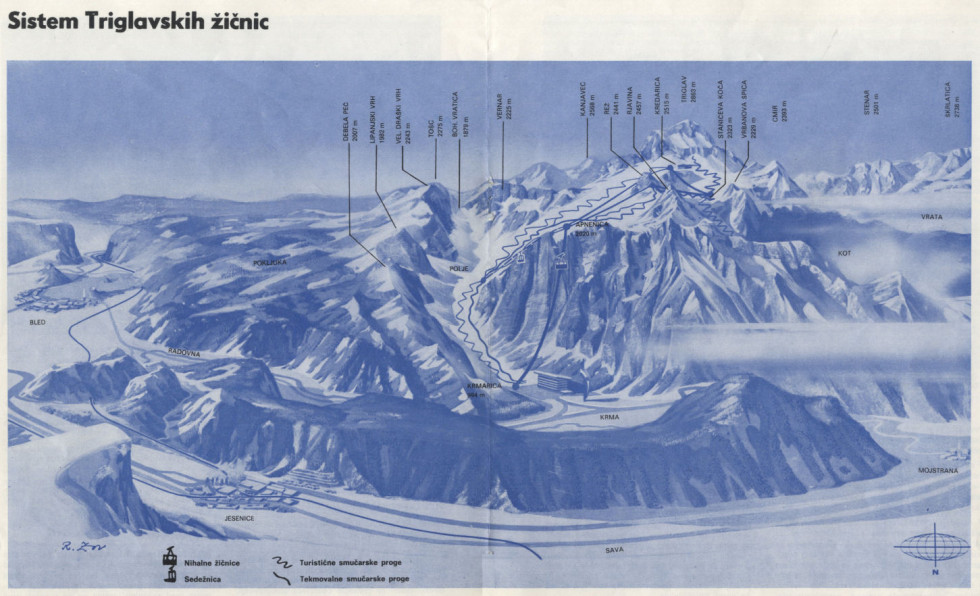

The expected outcome of the project was the construction of a circular system of gondola cabin lifts in the direction of Krmarica (994 metres above sea level) – Apnenica (2020 metres above sea level) – Kredarica (2515 metres above sea level) – the Stančič Hut (2332 metres above sea level) with return trip over Apnenica to Krmarica. The system of gondola lifts would furthermore be completed with ski lifts on Apnenica, the Stančič Hut and on the glacier itself. Restaurants, bars and accommodation capacities would be built at individual lift stops. Construction of such lifts would entail the building of access road to the Krma valley, arrangement of electrification and phone connections, control of mountain streams, construction of protection facilities together with alert systems for protection against avalanches.

Such major intervention in Slovenian highland and particularly in that part of the mountains that Slovenians were most proud of soon began to arouse strong opposition in newspapers, dividing pubic opinion to those in favour and those opposing the project. In the end, the project fell through due to lack of political will and realization of its developers that such activity would indeed be too much of an intervention into nature.

Jernej Križaj