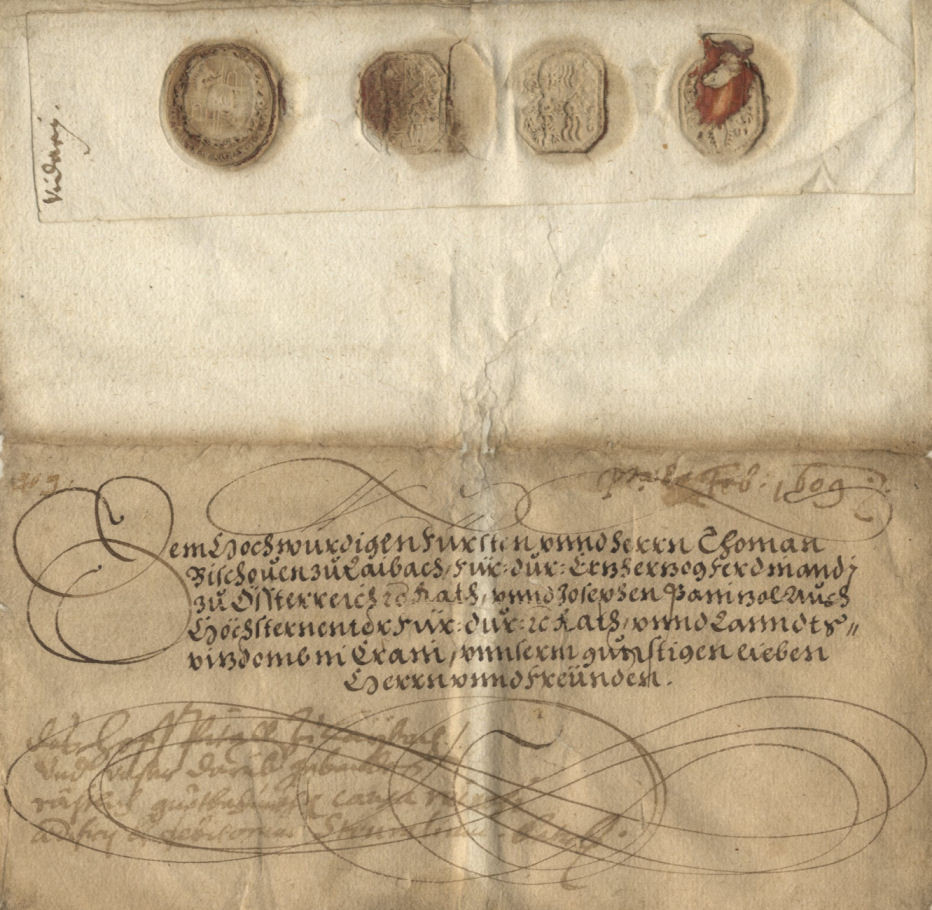

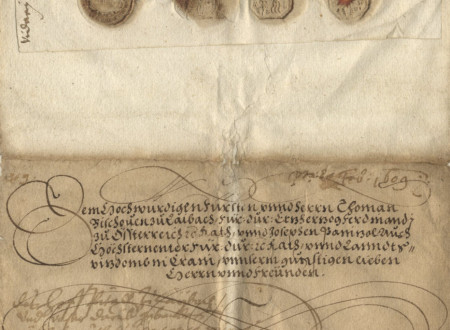

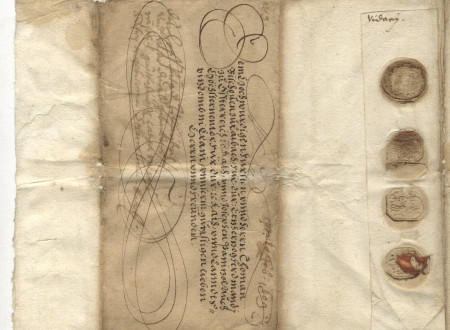

Request of the Inner Austrian Court Chamber Addressed to the Superintendents of the Emperor’s Court Hospital in Ljubljana, Asking for the Report on the Hospital’s Debt

Request of the Inner Austrian Court Chamber Addressed to the Superintendents of the Emperor’s Court Hospital in Ljubljana, Asking for the Report on the Hospital’s Debt

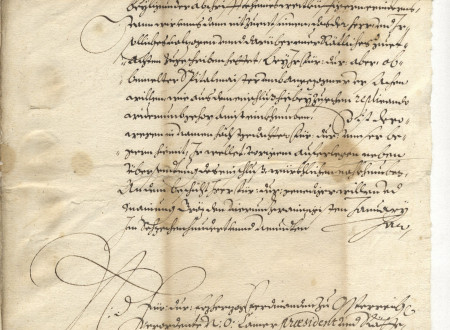

The request made four hundred and ten years ago by the Inner Austrian Court Chamber on behalf of the territorial prince Ferdinand II and sent to the Ljubljana bishop Tomaž Hren and to the Carniolan Vicedo Jožef Panitzol, is just one of many such calls, issued to determine the actual, not very promising, financial conditions of the Emperor’s Court Hospital in Ljubljana. The first among such requests was sent from Graz to Ljubljana on April 9, 1607, only to be followed by another one three months and a half later, on July 24, 1607. While these first two calls instructed the superintendents – Vicedom at the time was Filip Cobenzl – to prepare a report on the debt incurred during the office of the late hospital master Sigmund Ebenberger, the ones from 1609 clearly refer to the still very poor financial conditions of the hospital under the management of the then master Jakob Vidaz (Vidatius, Vidaz).

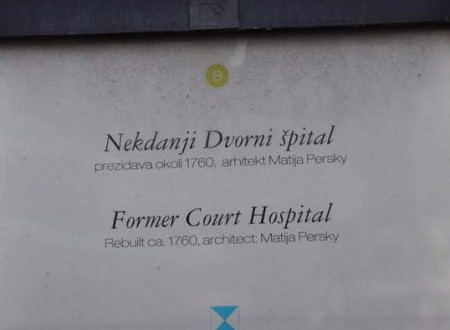

It is not surprising, though, that the authorities in Graz cared so much about how hospital property was being managed by those in charge. As is evident from the title “Emperor’s Court Hospital” (kaiserliches Hofspital), this was an institution established by the emperor, or, more precisely, by the Archduke and the later Emperor Ferdinand I (1521–1564, Archduke of Austria, 1558–1564 Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire). Tangible beginnings of the hospital date back to the mid-1550s and the signing of the contract, according to which the Augustinians, situated in St. James’ Church in Ljubljana, agreed to leave their monastery and their monastic property to Archduke Ferdinand before moving out of town, provided they were to obtain other property. Not long after that, the court hospital was forced to move twice; at the turn of the 17th century, when the premises at St. James’ Church were given to the Jesuits, and again in the first half of the 1620s, when the hospital had to move “across the street” to make room for the revived Franciscan monastery. For this purpose, two houses were purchased in today’s Vodnikov trg 5, where the hospital continued to operate for another 160 years. Today, the building itself bears a commemorative plaque, informing the public that it was rebuilt in 1760 by the architect Matija Persky.

Although the two superintendents were quick to respond to the request of the Inner Austrian Court Chamber from January 24, 1609, the subsequent two requests issued by the chamber on June 22 and 27, 1609, and addressed to bishop Hren and to Vicedom Pantizol reveal that authorities in Graz were not satisfied with their response. Their report was not considered exhaustive enough and they were also believed not to have taken a firm enough stand against the complaints of the hospital master Vidaz. Although Vidaz regularly submitted yearly balance sheets to Vicedom for confirmation, which was always received, by 1611 the Court Chamber in Graz was already thinking about appointing a new hospital master. The replacement was eventually carried out, despite Vidaz’s protest that it was he himself who lent the hospital 520 Gulden out of his own pocket. In 1612, Vidaz was discharged and replaced as the hospital master by Tomaž Reringer (Röringer), the man who sold one of the two above-mentioned houses to the hospital. Reringer, too, quickly found himself the target of criticism. A fair amount of records, preserved about the Ljubljana Court Hospital at the Archives of the Republic of Slovenia, reveal that problems were a common feature. Contained among the preserved records are a number of different complaints coming from both the hospital management and the occupants.

An important question, which is yet to be systematically researched, is a question of who was actually allowed to be admitted to the Court Hospital in Ljubljana. In the autumn of 1642, the then hospital master wrote that the hospital was not intended for the sick, but mainly for the elderly and the disabled. At the time, there were fourteen of those being treated at the hospital, nine women and five men. Forty years later, a letter was sent by the Inner Austrian Court Chamber, instructing the hospital’s superintendents (bishop Jožef Rabatta and Vicedom Franc Adam Ursini von Blagaj) to make sure that the first empty bed at the hospital be provided for Jurij Zajc, a seventy-eight-year- old miner from Idrija. During the first few decades of the 18th century, preference in hospital admission was apparently given to physically weak miners from Idrija and from other mines throughout the land, such as the ones in Kropa and Železniki. On the other hand, records show that by the mid-18th century, many of the occupants at the hospital were former soldiers. In 1745, the hospital provided care for seven former soldiers; the remaining two occupants were a former miner from Idrija and a son of an unnamed imperial employee (toll collector), who due to his serious illness was unable to support himself. Also residing at the hospital were a servant, a cook, a maid and a cow servant. At the time, three men decided admission of new occupants into the hospital: the bishop of Ljubljana, Carniolan provincial governor, and Carniolan provincial Vicedom.

Based on what has been stated above, we may conclude that the 410-year-old request issued by the Court Chamber in Graz to the two superintendents of the Court Hospital in Ljubljana is a tiny, but valuable piece in the mosaic of diverse archival notes on this provincial-princely institution. It is a source that, as has been pointed out, confirms the fact that the authorities in Graz (and later in Vienna) cared about the financial conditions of the court hospital – which, apart from the town hospital, was the only long-lasting health care institution in Ljubljana during the early Modern Times. Hopefully, the preserved archival records about the Ljubljana Court Hospital, most of which are yet to be researched, will soon find their way into the local and national historiography.

Lilijana Žnidaršič Golec