A Letter by the Czechoslovakian Minister of Justice Dr. Neuman to the Federal Secretary of Justice of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Regarding the Rehabilitation of Vekoslav Figar and Ivan Ranzinger

A Letter by the Czechoslovakian Minister of Justice Dr. Neuman to the Federal Secretary of Justice of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Regarding the Rehabilitation of Vekoslav Figar and Ivan Ranzinger

This year marks seventy years since the judgement of conviction in the “Eight Dachau Trial” was delivered, when on June 29, 1949, under reference number K 155/49, Ivan Ranzinger and Vekoslav Figar were sentenced at the Ljubljana District Court to 18 and 15 years in prison respectively. The indictment charged them with “provocations” at the Buchenwald concentration camp, where they were believed to have been members of a “criminal organization” that cooperated with the Gestapo. A glass worker by profession, Ivan Ranzinger was a communist before WWII and was during the war taken by the Germans first to Auschwitz and then to Buchenwald concentration camp. After the war and up until his arrest, he was an active member of the Communist Party of Slovenia, working as an organization secretary of the Party’s committee in Trbovlje. Vekoslav Figar was a lawyer, an active member of the Liberation Front during the war, who was later taken to Dachau concentration camp. Ranzinger was released after serving four years in prison, and Figar a year later. Although Ranzinger was pardoned in 1962 and Figar in 1968, their guilt was not erased. Both of the accused called for the revision of their cases several times, but their appeals were continuously dismissed by the competent authorities in Ljubljana.

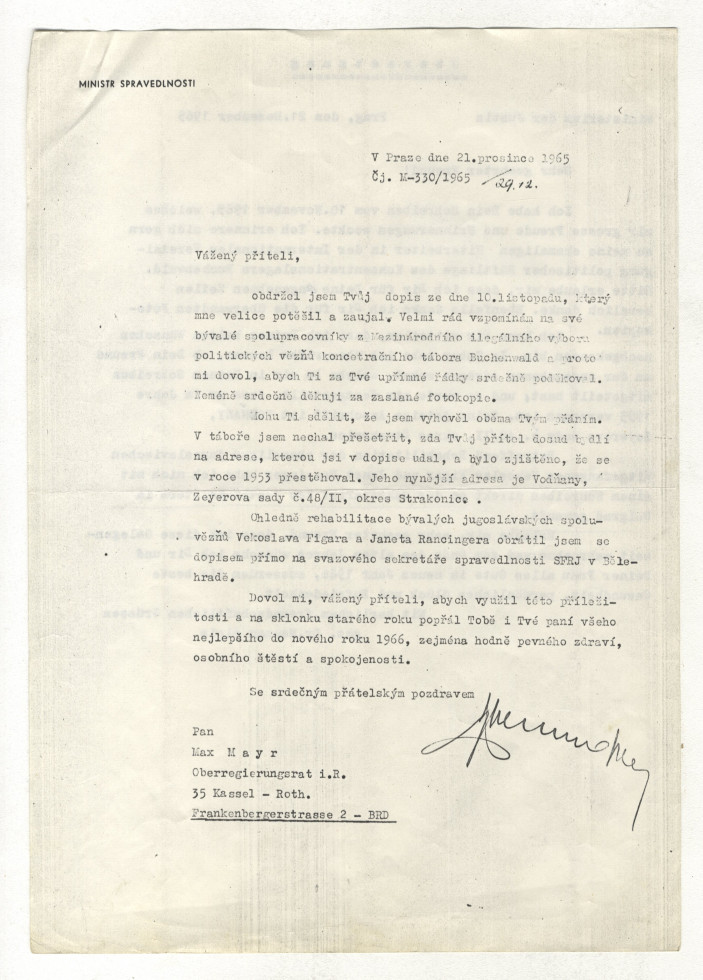

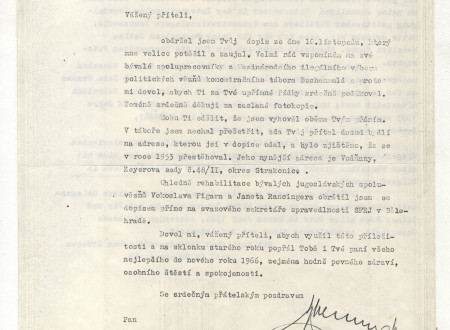

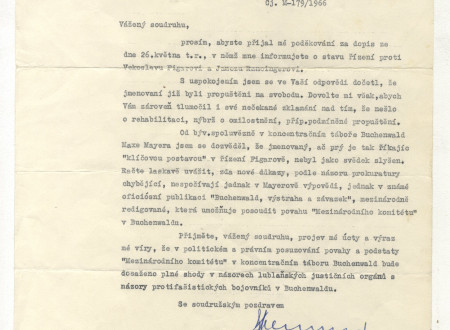

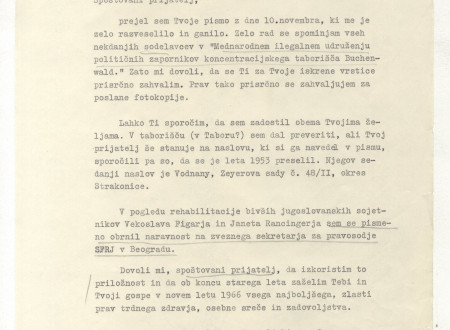

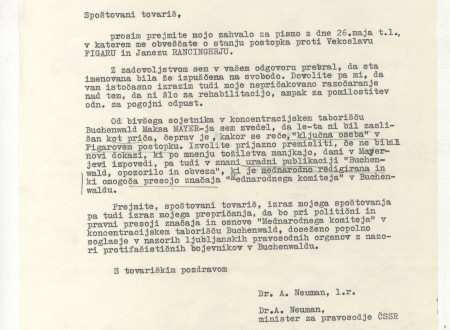

This month’s archivalia is a letter sent by the Czechoslovakian Ministry of Justice Dr. Alois Neuman to the Federal Secretary of Justice of SFRJ Milorad Zorič on August 6, 1966. The letter makes it evident that Dr. Neuman had been monitoring the situation of the two men convicted at the eight Dachau trials for quite some time. He expressed his deep disappointment over the fact that the two men were merely pardoned (Figar even only conditionally discharged), and not fully rehabilitated. Enclosed is a letter sent by Neuman in December 1965 to Max Mayr, the retired senior government counsellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, which shows that the latter had also been interested in the state of the proceedings against the two convicts.

“Dachau trials” attracted the interest of Yugoslav and international public already in the 1960s. Even the Communist Party of Austria made several demands, like the one in their 1969 letter, to re-evaluate the circumstances based on which Ranzinger and Figar were convicted, focusing mainly on those parts of the conviction which stated that national and international committees, led by the communists in concentration camps, were “criminal organizations”. These organizations were supposed to have been working under direct leadership of the Austrian, German and other communists, who continued to be the leading members in the communist parties of their respective states long after the war ended. One of them was Max Mayr, a distinguished German politician and socialist, who in the indictment against Figar and Ranzinger was characterized as being a Gestapo agent, against whom no criminal procedure was initiated after the war and who for a long time continued to occupy high political position in Germany. Perceived as a devoted antifascist and an internationalist by numerous surviving Russian and other European internees, Mayr was also one of the major initiators for rehabilitation of the two convicted men, since the indictment against them was based on the belief that he was the leader of a “criminal organization”. Also emphasizing the international importance of “Dachau Trials” was Dr. Rudi Super, who in 1965 submitted his request for the revision of the trial against Ranzinger and Figar. In addition to “Nadoge trial”, “Dachau trials” stood out from the rest of post-war court trials in that the accused here belonged to the same political party and ideology and were tried based on fake accusations. This was typical of trials in Stalinist Soviet Union, where such proceedings were justified as a necessary measure to protect the state, the teachings of Marx and Lenin, and the proletariat. Although seen as one of the versions of the Stalinist trials by some of the historians who researched this subject, such trials in Slovenia nevertheless constituted a “Slovenian particularity”. There were numerous initiatives of the Slovenian public for retrial, some of them even addressed directly to Tito.

The document presented here is of considerable significance, especially if we take into consideration the fact that Czechoslovak Republic, which was a state governed by the Communist regime, expressed its unpleasant surprise over the fact that Yugoslavia, a state believed to have “a more friendly form of communism”, failed to rehabilitate both convicted men, but merely pardoned them or even just began a process of pardoning them. The document is important also because it proves the campaign for retrial was started by Max Mayr, a former foreign internee and a retired German senior government counsellor. Namely, the document makes it evident that Mayr asked for mediation with Yugoslav authorities regarding rehabilitation of his two former co-internees already prior to December 1965. However, despite receiving initiatives from Slovenian former internees and other members of domestic public, Slovenian judiciary initiated proceedings for the annulment of conviction only after foreign states, also communist ones, intervened.

With its court order of November 26, 1970, the Supreme Court of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia granted a request of the public prosecutor of SRS for a retrial of the 1949 criminal procedure, which saw Vekoslav Figar and Ivan Ranzinger sentenced to several years in prison. On January 19, 1971, before the trial, the public prosecutor of SRS withdrew the charge of the public prosecutor’s office of Ljubljana district from June 6, 1949 against the two defendants. Criminal procedure against Vekoslav Figar and Ivan Ranzinger was stopped on January 29, 1971, and the 1949 judgement was reversed.

Aida Škoro Babić